|

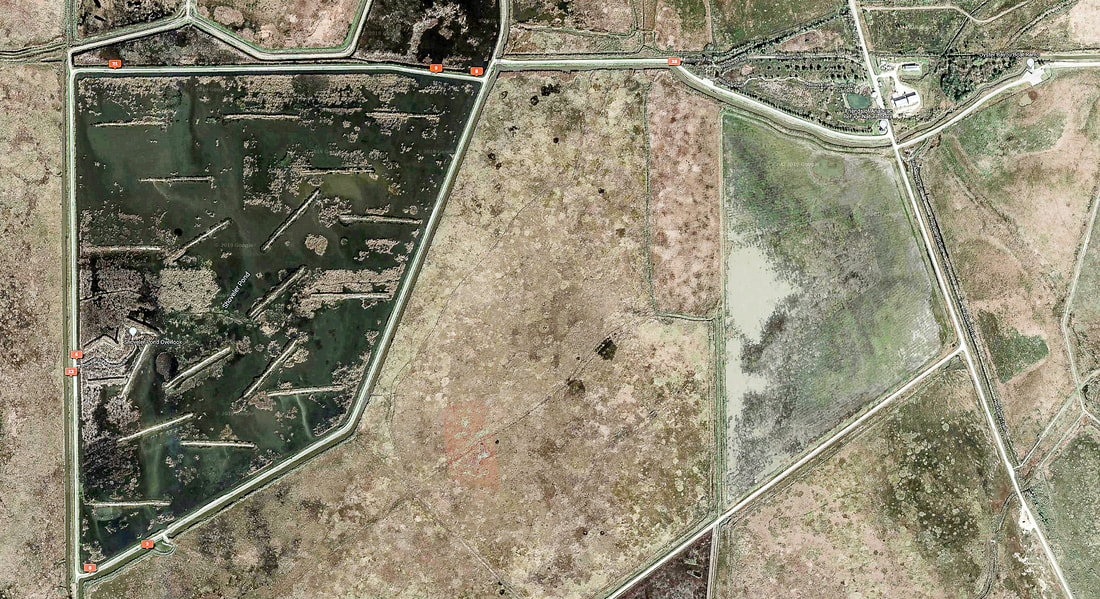

For those of you that follow this blog, my last two entries were from our trip to the Texas coast in late April, first on the Smith Oaks Rookery in High Island, and next a very entertaining Reddish Egret doing his antics to scare up some lunch. This post focuses on one day, April 27th, when we visited the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. This 37,000-acre refuge occupies much of the center of the map below. To provide some orientation, and help you plan a trip to the area, High Island is in the lower right corner of the map, and Rollover Pass is lower center, with the Anahuac refuge directly north. The 37,000-acre refuge was established in 1963 as part of the National Wildlife Refuge System. For more on this system, and locations near you, click here. The Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge was established on ancient flood plains, with vast expanses of coastal marsh and prairie bordering Galveston Bay. The refuge is home to both local and migratory birds, as well as alligators (See lead photo!) and other wildlife. The morning of the 27th we drove in from the north, stopping by open fields, then toured Shoveler Pond, detail map below. The red marks indicate places where images were captured. The GPS chip in the Canon 7D Mk II make this possible when combined with Adobe Photoshop Lightroom's mapping feature. Note that in April the Shoveler Pond Boardwalk was closed for repairs, but is open as of June 18th. Orchard OrioleOrioles are in the family Icteridae (Icterids), one of 137 families in the Order Passeriformes, also known as perching or song birds. The Icterids are New World Passerines, and consist of 29 genera, and include orioles, blackbirds, meadowlarks, grackles, and cowbirds. Orioles are in the genus Icterus, which includes 33 species, including the Orchard Oriole, Icterus Spurius. We spotted this male, and a female, as we entered the refuge from the north, and were fortunate to get good views in good light. The males are black above, and reddish/chestnut below. Orchard Orioles winter from Mexico south into northern South America, and breed from Texas and the southern states to Canada, east of the Rockies. The birds we see here could be breeding on the Texas coast, or are on their way north, and have stopped for a quick bite. They eat mostly insects and other arthropods, along with some fruit and nectar. Below is a female, olive above, yellow below. At this point I cannot avoid jumping away from the Texas coast for a moment, and digging into my archive of oriole images to take a peak at Baltimore, Hooded, Scott's and Bullock's Orioles, with this bold disclaimer: The following images of orioles were not taken in Texas! (Just so no one is confused!)Baltimore Oriole, male, captured at his nest on the shore of Squam Lake, New Hampshire, May 2019 (yes, we went to New Hampshire after Texas.) This sock-like hanging nest is typical of the species, carefully woven by the female. Here the male appears to be standing guard. Hooded Oriole, male, captured at Agua Caliente Park in Tucson Arizona, May 2017. Scott's Oriole, male, taken at Battiste Bed, Breakfast and Birds, Hereford, AZ, March 2018. Bullock's Oriole, male, at Agua Caliente Park, May 2017. OK, back to Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge . . . .Eastern KingbirdThe Eastern Kingbird, Tyrannus tyrannus, is one of over 300 species in the Tyrannidae family, Tyrant Flycatchers. They winter in South America and migrate in flocks to North America, generally avoiding Arizona and the Pacific Coast. This bird could be a Texas resident, or a migrant resting on the coast before continuing the trip north. They are handsome birds looking ready for a formal evening event. This bird was spotted on a wire near the road, not far from the Orchard Oriole above. Click this link to browse the Tyrant Flycatchers on the Cornell Lab website. Speaking of flycatchers, here are some images of a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher we spotted on Galveston Island on the 29th. These are beautiful birds with very long tails. We were fortunate to catch this bird on the wire, but did not catch any in flight. They breed in the central south U.S. from Texas into Oklahoma and Kansas, wintering in Mexico and Central America. For the photo geeks out there: This image is "soft" in part because of the high ISO (~2500), but largely because it was shot through the side window of the van. The window did not open, and getting out of the van and keeping the bird on the wire did not seem a reasonable option. Here I decided that a "soft" image was better than no image at all. DickcisselDiskcissel's are grassland buntings in the cardinal family, wintering in Central and South America, and breeding in the prairie midwest. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology website provides this wonderful description: "The curt song of the Dickcissel sounds like the bird’s name, and it’s part of the soundtrack of the North American prairies. This chunky grassland bunting is colored like a miniature meadowlark, with a black V on a yellow chest. These birds are erratic wanderers—common across the middle of the continent, and a pleasant surprise whenever they turn up in pastures and fields elsewhere in the central and eastern United States. Dickcissels can form enormous flocks on migration and in winter." It seems likely that this bird is in migration. Photo geek note: These images were also shot through the side window of the van. A Glossy Ibis on Shoveler PondThe Glossy Ibis is in the family Threskiornithidae, consisting of 34 species worldwide, with 4 in North America: the Glossy Ibis, White-faced Ibis, White Ibis, and Roseate Spoonbill. We saw the spoonbill in a prior post on the Smith Oaks Rookery, and we will see the White Ibis below. Shoveler Pond is an extensive wetland that is part of the park, and detailed in the second map at the top of this post. Below is a view from the perimeter road, including the viewing platform which was being repaired during our visit, but is open now. The Glossy Ibis above was off in the distance on the pond, but I was able to capture closer images of the same species on the 29th on Galveston Island, below. Breeding adults have chestnut plumage glossed with green or purple. All plumages have a powder blue line on the face that does not completely encircle the eye, detail in 4th frame below. (Reference: National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, 7th Edition, Dunn and Alderfer, p 266.) This bird is preening, showing long legs and decurved bill. Eye detail below. White Ibis, first springAbove, on Shoveler Pond, is a White Ibis in the first spring. The adult is white with a pink/red face and white eye. The juvenile has a dark eye and dark back, but as it matures, in the first spring, distinctive white feathers come into the back with a mottled neck (Reference: National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, 7th Edition, p. 266) Both Glossy and White Ibises have similar foraging habits, using their long bills to probe for fish and crustaceans in the mud. Their range is similar, coastal marshes and wetlands of the southeast U.S with Glossy Ibises going up into New England, and White Ibises into Mexico. King RailAs we got closer to Shoveler Pond, we spotted two photographers with some serious telephoto gear intent on the edge of the reeds. We joined them and over time spotted a King Rail in reasonable light looking for food along the water's edge. King Rails are in the Rallidae Family along with Sora, Gallinules, and Coots. The King Rail lives near fresh water marshes and swamps from Mexico into New England. Their population has been declining in recent years, most likely due to loss of habitat and pesticide use. They are on the 2014 State of the Birds Watch List as being threatened or endangered without conservation efforts. This rail is 12 to 14 inches in length. Although there are no yardsticks in the wild, we do see the bird adjacent to a tree stump that is probably 4 to 5 inches in diameter. King Rails eat crustaceans, especially crayfish, as well as aquatic insects, and small fish. Virginia RailWe stopped at Brazos Bend State Park on April 30th, the last morning of our trip. This Virginia Rail was foraging among the reeds in reasonable light. Unlike the King Rail, the Virginia Rail lives throughout North America, wintering in the southern U.S. and Mexico and breeding north centrally all the way up into Canada. This rail is smaller than the King Rail, and has grey cheeks, a reddish bill, and cinnamon neck. It is said to be larger than a Sora, and smaller than an American Coot. We get an estimate of this bird's size from these images, where we can compare the size of the bird to adjacent reeds and stumps. Ohhhh, don't forget the Alligators !There are lots of American Alligators throughout the freshwater wetlands of SE Texas, and Shoveler Pond is no exception. Above, an American Alligator waiting for lunch to arrive. Below, an exercise in image recognition. Let's see, from top to bottom: log, log, . . log-log. . . . .log, log, . . . . sea weed. . . . . loooo . . . nooooo....ALLIGATOR! They do look like floating wood. The portions of head and back that show above water belie their full size. Below, an American Allligator out of the water getting some Texas sun. Below, a close up. Imagine just the nose, eyes, and top of back above water. There is a lot of alligator below water, with a big mouth, and massive jaws and teeth. Definitely no swimming in Shoveler Pond, and best not to fall into the water! That's it for Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. More posts soon. Happy trails!

2 Comments

|

AuthorHenry Johnson, photographer and author of this site. For more detail, see About

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed