|

Anhinga, Brazos Bend State Park, April 2019. The Bolivar Ferry to Galveston . . . . . .Magnificent FrigatebirdOn Monday April 29th we drove the vans onto the Bolivar Ferry to Galveston. As I got out of the van, I had the option of leaving my camera in the van, or lugging it up the companionway to the upper deck where everyone was congregating. Being a proponent of "never leave your camera behind," I took it with me - that really great shot was never captured by a camera left at home or locked up in a car. I hung out in the stern and grabbed some really bad photos of Laughing Gulls looking for food in the wake, when someone on the starboard side yelled, "Magnificent Frigatebird!" I walked around to the starboard rail, and sure enough, there was a frigatebird. See images above and below. Magnificent Frigatebirds have a deeply forked tail, and pointed wings. Here we see a female with a dark head and a white breast patch. The males have red gular sac (throat) most visible in the breeding season. They are known for aerobatics, catching their food in flight, commonly flying fish just above the water. The Magnificent Frigatebird, along with its cousin the Great Frigatebird, are in the Frigatebird Family, sharing the order Suliformes with the Boobies and Gannets, Anhingas, and the Cormonants and Shags. Unlike Cormorants, the Magnificent Frigatebird is most at home in the air, and does not sit on the water or swim. They breed in coastal areas of the southern U.S., Mexico, Central and South America including the Galapagos Islands. It was fun to see this bird in the channel. And, yes, I was glad I lugged my camera around the ferry! Galveston Island: Seaside SparrowOn Galveston Island we spotted this Seaside Sparrow in the grasses. The Seaside Sparrow is a habitat specialist of salt and brackish marshes. Occurring in relatively small, localized populations along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States, this species has been divided into several morphologically distinct subspecies. They nest in marshes with expanses of medium-high cordgrass with a turf of clumped, residual stems. Especially suitable are spots not subject to extreme flooding that have open muddy areas for feeding. Nest mortality is due to storm flooding as well as predation. (Ref: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology). As a maritime wetland specialist, the Seaside Sparrow is a potentially valuable “indicator” of ecological integrity of certain types of coastal marshes and has already proven sensitive to habitat modification in Florida. (Ref: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology). Brazos Bend State Park: AnhingaBrazos Bend State Park is on the Brazos River, about one hour drive from Houston. It offers recreational facilities as well as ponds and marshes for wildlife, with elevated walkways for viewing. This Anhinga was perched in a tree preening, then took flight. The morning was overcast, not uncommon for this trip, but the sun did come through long enough to provide some good light for these images. The Anhinga is a striking bird, with a long s-shaped neck, dagger-like bill, and fanlike tail. An aquatic species, it spends its life in water or on branches overhanging protected, usually freshwater streams and ponds. They have fully wettable plumage and dense bones, allowing them to stalk and spear fish while staying partially submerged in the water. Like cormorants, they need to dry their wings in the sun. The male Anhinga took flight. It appears that he is missing one primary flight feather on the right. Note the distinctive tail, which has been compared to the tails of turkeys. Little Blue HeronStalking the marsh at Brazos Bend was a Little Blue Heron, a small heron decked out in moody blues and purples. They live in the marshes and estuaries of the Southeast, eating small fish and amphibians. Here we see their slow methodological approach to hunting. Last frame show success, a crawdad for breakfast! Little Blue Herons build stick nests in trees alongside other colonial waterbirds. In the U.S., their populations have been in a gradual decline since the mid-twentieth century. Little Blue Herons may gain a survival advantage by wearing white during their first year of life. Immature birds are likelier than their blue elders to be tolerated by Snowy Egrets—and in the egrets’ company, they catch more fish. Mingling in mixed-species flocks of white herons, immature Little Blue Herons probably also acquire extra protection against predators. Below a series of images of an immature bird in fight. Note: In the first, third and fourth frames above we can see the alula, two feathers projecting from the edge of the wing. This is the bird's equivalent of the human thumb, sometimes referred to as the bastard wing. It is deployed in flight much like an airplane deploys slats on the forward wing, to deflect airflow over the wing itself to increase lift, especially at slow speed and when the wing is angled up to slow flight. The alula, like slats on a plane, prevent stalling at slow speeds. Without it, birds would either have to land at faster speeds, or would stall, suddenly dropping to the ground when landing. For more images of the alula, see my post on the American Kestrel at Ft Lowell Park, New Year's Day 2018. Purple GallinuleThe Purple Gallinule is among the most gaudy breeding birds in North America. Richly colored with deep blue, green, and purple and trimmed with red, yellow, and sky blue, this fresh-water wetland species has proven adaptable to habitat modification, thriving in natural as well as human-made plantations and refuges. It lives in marshlands in the southeast U.S. as well as coastal Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, eating a variety of foods including flowers and fruits of the water-lily family, as well as invasive exotic plants and rice. Although primarily plant eaters, they also eat spiders, mollusks, beetles, bees, worms, snails, dragonflies, leeches, ants, grasshoppers, and moth larvae, as well as frogs, small fish, and eggs and nestlings of other birds. (Ref: All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology). Here we see a Purple Gallinule taking long strides through the marsh looking for food. Their long toes are well suited for either marsh walking or clinging to vegetation.

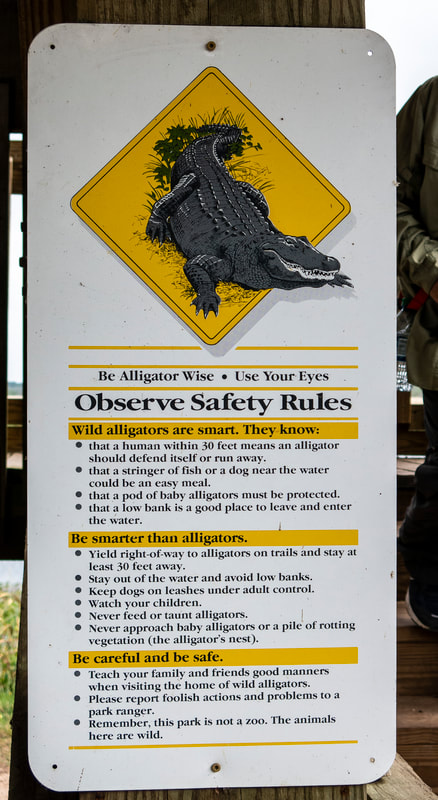

American Alligators, once headed for extinction, are now in abundance in rivers, lakes, swamps and marshes of the southeastern U.S. We saw them throughout SE Texas on this trip, wherever there was fresh water. Heavy and ungainly out of water, these reptiles are supremely well adapted swimmers. Males average 10 to 15 feet in length and can weigh 1,000 pounds. Females grow to a maximum of about 9.8 feet. They feed mainly on fish, turtles, snakes, and small mammals. However, a hungry alligator will eat just about anything, including carrion, pets and, in rare instances, humans. [Ref: National Geographic] The alligators at Brazos Bend are very close to the pathways, and often will walk across them, or sun themselves on a path. The park has many posted warning signs, one of them above. Below, an alligator at Brazos Bend. For more alligator images, see this posting on Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. This is the last post, Part V of V, on the Texas trip! I want to express my concern for all those in east Texas affected by the recent flooding from tropical storm Imelda. During our trip in April we stayed two nights in Winnie, and traveled in and out of areas that were completely covered with water from this recent storm. Brazos Bend State park likely flooded as well. The American Red Cross is active in east Texas, and provided temporary shelter for many. If you would like to contribute for aid to those affected by the flood, go to this link for the American Red Cross. Thank you! Happy Trails!

0 Comments

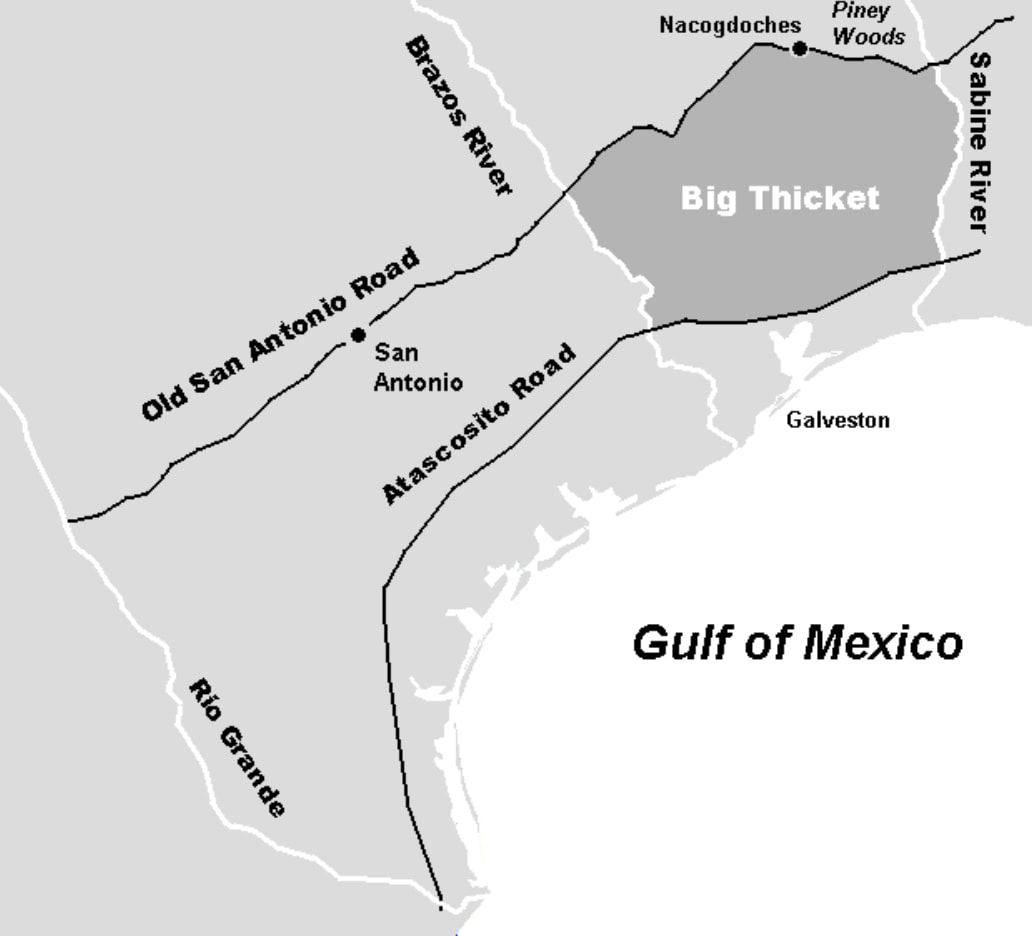

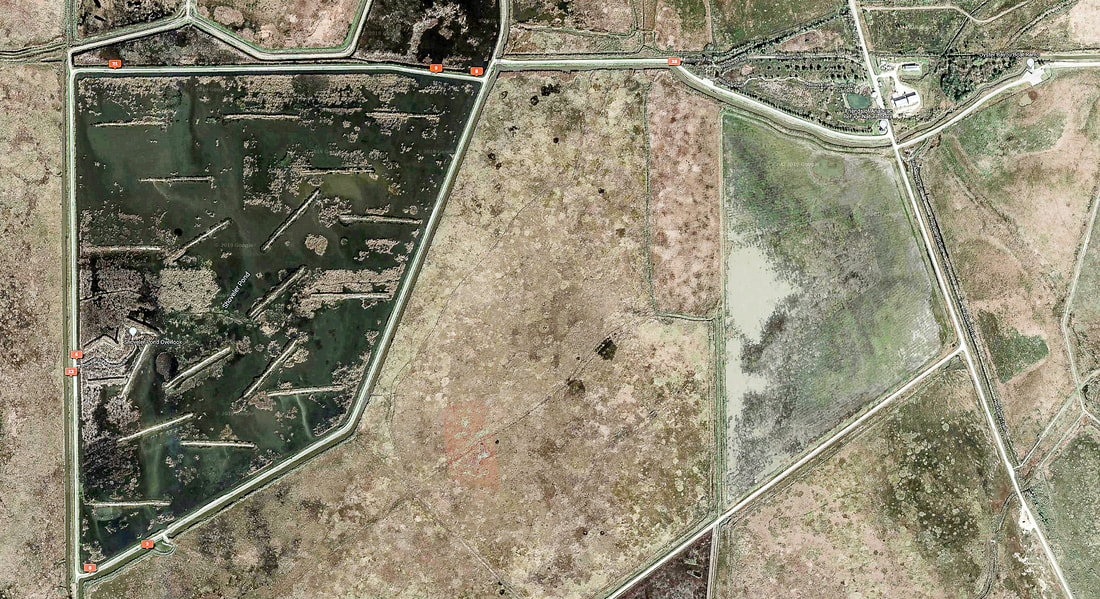

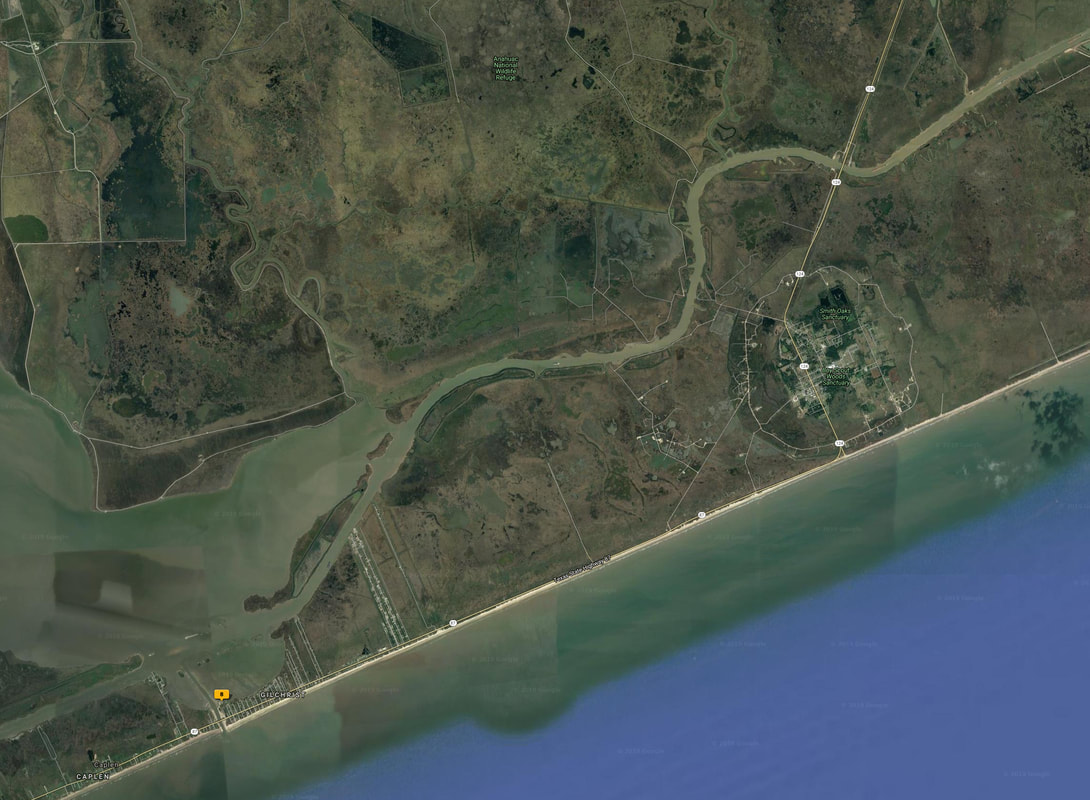

Kentucky Warbler, Big Thicket Happy Fall! It has been a busy summer, and the blog has been quiet, but now is the time for me to catch up by completing the last two posts for the Texas Coast followed by more on Mt Lemmon! The first three Texas coast posts covered the Smith Oaks Rookery at High Island, a Reddish Egret dancing for his lunch on Galveston Bay, and the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. Today we are going to the Big Thicket, then south back to High Island and Boy Scout woods. Part V (coming soon) will take us on the ferry from Bolivar Peninsula to Galveston, and then to Brazos Bend State Park. Prairie WarblerJust north of Big Thicket National Preserve (BITH) is the Angelina National Forest where we spotted this Prairie Warbler on a branch. Prairie Warblers winter in coastal Central America, southern Florida, Cuba and the Caribbean, and breed in the eastern U.S. as far north as Massachusetts. Both winter and summer they favor regenerating forests and dunes and shrubby old fields. [Ref: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology]. These images were captured early in the morning in very low light with overcast skies, at some distance, accounting for the soft quality. Kentucky WarblerSouth of the Angelina National Forest we entered the Big Thicket, and the Big Thicket National Preserve. The Big Thicket is a large area of very dense forest, considered one of the most biodiverse areas in the world outside of the tropics. The preserve was established in 1974 to protect the many plant and animal species within. The original area covered more than 2 million acres in east Texas. The map below shows the boundaries as defined by the Spanish settlers before the Texas Revolution (1835). The area has a rich and colorful history. Its dense and almost impenetrable center became the preferred place "to disappear" beginning with confederate deserters during the Civil War. Before deforestation, it was said to be so dense that sections could only be accessed by crawling in on hands and knees. It was said that "if a snake crawls in, it has to back out." Historical limits of the Big Thicket prior to the Texas Revolution in 1835. Ref: Wikipedia. This Kentucky Warbler was spotted at some distance from the trail, above the understory and in good light. Kentucky Warblers are ground-nesting birds, generally staying low in the understory, heard more often than seen. However, this is spring, when males take to the heights and sing motionless for 5-15 minute sets. They winter in Central America, breeding in the eastern U.S. This bird is likely in migration, heading to Missouri or Illinois. [Ref: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology] Yellow-breasted ChatThe Yellow-breasted Chat winters in Central America and coastal Mexico, migrating north to breed from California to the eastern seaboard. This chat favors low, dense vegetation without a closed tree canopy, including shrubby habitat along streams, swamps, and ponds. Richard Taylor's field guide Birds of Southeastern Arizona lists the Yellow-breasted Chat as a summer resident in SE Arizona below 5000 feet. It prefers dense brushy areas, which combined with its secretive nature, make it hard to spot. Here we see what is likely a male singing his heart out on a pine branch. The Yellow-breasted Chat was previously placed in the family Parulidae, but in 2017, was elevated to its own family, Icteriidae (Chesser et al. 2017). [Ref: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology] For the photo geeks out there, again, early morning, low light, milky sky. Whooping Cranes!OMG, a pair of Whooping Cranes! On the way to High Island, our guide Bob Behrstock followed up on a report of two Whooping Cranes in a nearby agricultural field. Here they are, likely a male and a female, with radio transmitters on their legs, one transmitter on the right (maybe the male) and one on on the left. The Whooping Crane has become a symbol of national and international efforts to recover endangered species, returning from the brink of extinction, but remaining at risk. In 1941, the species reached a low of 15 or 16 migratory individuals wintering in Texas and 6 non-migratory birds in Louisiana. Even with intense management efforts, the Whooping Crane remains one of the rarest birds in North America, and on the Endangered Species list. It remains ecologically dependent on inland freshwater wetlands and, in winter, on coastal brackish wetlands. These birds may be part of a year round population that lives in Louisiana who decided to forage a bit west of home, or they may be on their way back to their breeding ground in Canada from wintering ground further south on the Texas coast. Both birds have radio transmitters on their legs, detail below. Whooping Cranes are in the same family as Sandhill Cranes, who are regular winter residents of SE Arizona and New Mexico. See my posts from White Water Draw and Bosque del Apache. Reference: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Blue GrosbeakOn the way to High Island, just south of Winnie, we spotted a Blue Grosbeak, a large bunting often seen singing from roadside wires and tree tops. The Blue Grosbeak is in the family Cardinalidae along with other Grosbeaks, Tanager’s, the Northern Cardinal, the Pyrrhuloxia, other buntings and the Dickcissel. It feeds on insects, especially grasshoppers and crickets, as well as the seeds of wild and cultivated grains. They nest in shrubs or tangles of vines along the forest edge or roadside. This bird is likely in migration to the southern U.S. from wintering grounds in southern Mexico and Central America, making the trek across the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Indigo BuntingArriving on High Island we spot an Indigo Bunting sitting on a wire by the side of the road. The Indigo Bunting is another member of the Cardinalidae family. This small bunting winters in Mexico and Central America, flying north to breed in the U.S., east of the great plains. This bird is likely in transit. Indigo Buntings live in shrubby areas and weedy fields. They eat seeds, berries and insects, and in migration, mainly seeds of grasses, as we can see in these images. Note that this male has grabbed the top of the grass with the seeds, along with the wire. Looks like corn on the cob. Rose-breasted GrosbeakAt High Island we found a Rose-breasted Grosbeak, another member of the Cardinalidae family, hopping in and around a mulberry tree, feasting on the fruit. They winter in Central and South America, and migrate long distances north to breed in the eastern and mid-United States and into Canada. This is definitely a migrant, stocking up on food after the long flight across the gulf. Chuck-wills-widowHiding out napping in a secluded spot in a tree, we found a Chuck-will's-widow, saving up his energy for an active evening of hunting insects. They hunt at dawn and dusk, flying low to the ground and catching insects, and an occasional bird. They will forage later into the evening under the light of a full moon. Their name comes from the continuous, repetitive song often heard at night. These birds live in the southeast U.S. wintering in Florida, Cuba, and Central America. Chuck-will's-widow is in the family of Nightjars and Allies, along with the Common Nighthawk (see last entry below), other Nighthawks and Nightjars, and the Eastern and Mexican Whip-poor-will. The family is in the Order Caprimulgiformes along with the Swift Family, and all the hummingbirds. There are big gaps in our knowledge of this species, especially about habitat and breeding success. Sounds like an opportunity for a graduate student who likes working at night! I have to admit that to my eye these birds look like hamsters with wings! They are the biggest Nightjar in North America. Common NighthawkMy last offering from High Island, a Common Nighthawk perched on a wire. The Common Nighthawk winters in South America and breeds throughout the U.S. and Canada, giving this species one of the longest migration routes of any North American bird. This bird could be in migration or may be getting ready to nest. Common Nighthawks are often observed on the wing at dusk or dawn grabbing insects in both urban and rural areas. They nest on open ground, gravel beaches, rocky outcrops, and burned-over woodlands, as well as flat gravel roofs, especially in cities. That's it for Part IV. Part V coming soon! Happy Trails! For those of you that follow this blog, my last two entries were from our trip to the Texas coast in late April, first on the Smith Oaks Rookery in High Island, and next a very entertaining Reddish Egret doing his antics to scare up some lunch. This post focuses on one day, April 27th, when we visited the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. This 37,000-acre refuge occupies much of the center of the map below. To provide some orientation, and help you plan a trip to the area, High Island is in the lower right corner of the map, and Rollover Pass is lower center, with the Anahuac refuge directly north. The 37,000-acre refuge was established in 1963 as part of the National Wildlife Refuge System. For more on this system, and locations near you, click here. The Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge was established on ancient flood plains, with vast expanses of coastal marsh and prairie bordering Galveston Bay. The refuge is home to both local and migratory birds, as well as alligators (See lead photo!) and other wildlife. The morning of the 27th we drove in from the north, stopping by open fields, then toured Shoveler Pond, detail map below. The red marks indicate places where images were captured. The GPS chip in the Canon 7D Mk II make this possible when combined with Adobe Photoshop Lightroom's mapping feature. Note that in April the Shoveler Pond Boardwalk was closed for repairs, but is open as of June 18th. Orchard OrioleOrioles are in the family Icteridae (Icterids), one of 137 families in the Order Passeriformes, also known as perching or song birds. The Icterids are New World Passerines, and consist of 29 genera, and include orioles, blackbirds, meadowlarks, grackles, and cowbirds. Orioles are in the genus Icterus, which includes 33 species, including the Orchard Oriole, Icterus Spurius. We spotted this male, and a female, as we entered the refuge from the north, and were fortunate to get good views in good light. The males are black above, and reddish/chestnut below. Orchard Orioles winter from Mexico south into northern South America, and breed from Texas and the southern states to Canada, east of the Rockies. The birds we see here could be breeding on the Texas coast, or are on their way north, and have stopped for a quick bite. They eat mostly insects and other arthropods, along with some fruit and nectar. Below is a female, olive above, yellow below. At this point I cannot avoid jumping away from the Texas coast for a moment, and digging into my archive of oriole images to take a peak at Baltimore, Hooded, Scott's and Bullock's Orioles, with this bold disclaimer: The following images of orioles were not taken in Texas! (Just so no one is confused!)Baltimore Oriole, male, captured at his nest on the shore of Squam Lake, New Hampshire, May 2019 (yes, we went to New Hampshire after Texas.) This sock-like hanging nest is typical of the species, carefully woven by the female. Here the male appears to be standing guard. Hooded Oriole, male, captured at Agua Caliente Park in Tucson Arizona, May 2017. Scott's Oriole, male, taken at Battiste Bed, Breakfast and Birds, Hereford, AZ, March 2018. Bullock's Oriole, male, at Agua Caliente Park, May 2017. OK, back to Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge . . . .Eastern KingbirdThe Eastern Kingbird, Tyrannus tyrannus, is one of over 300 species in the Tyrannidae family, Tyrant Flycatchers. They winter in South America and migrate in flocks to North America, generally avoiding Arizona and the Pacific Coast. This bird could be a Texas resident, or a migrant resting on the coast before continuing the trip north. They are handsome birds looking ready for a formal evening event. This bird was spotted on a wire near the road, not far from the Orchard Oriole above. Click this link to browse the Tyrant Flycatchers on the Cornell Lab website. Speaking of flycatchers, here are some images of a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher we spotted on Galveston Island on the 29th. These are beautiful birds with very long tails. We were fortunate to catch this bird on the wire, but did not catch any in flight. They breed in the central south U.S. from Texas into Oklahoma and Kansas, wintering in Mexico and Central America. For the photo geeks out there: This image is "soft" in part because of the high ISO (~2500), but largely because it was shot through the side window of the van. The window did not open, and getting out of the van and keeping the bird on the wire did not seem a reasonable option. Here I decided that a "soft" image was better than no image at all. DickcisselDiskcissel's are grassland buntings in the cardinal family, wintering in Central and South America, and breeding in the prairie midwest. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology website provides this wonderful description: "The curt song of the Dickcissel sounds like the bird’s name, and it’s part of the soundtrack of the North American prairies. This chunky grassland bunting is colored like a miniature meadowlark, with a black V on a yellow chest. These birds are erratic wanderers—common across the middle of the continent, and a pleasant surprise whenever they turn up in pastures and fields elsewhere in the central and eastern United States. Dickcissels can form enormous flocks on migration and in winter." It seems likely that this bird is in migration. Photo geek note: These images were also shot through the side window of the van. A Glossy Ibis on Shoveler PondThe Glossy Ibis is in the family Threskiornithidae, consisting of 34 species worldwide, with 4 in North America: the Glossy Ibis, White-faced Ibis, White Ibis, and Roseate Spoonbill. We saw the spoonbill in a prior post on the Smith Oaks Rookery, and we will see the White Ibis below. Shoveler Pond is an extensive wetland that is part of the park, and detailed in the second map at the top of this post. Below is a view from the perimeter road, including the viewing platform which was being repaired during our visit, but is open now. The Glossy Ibis above was off in the distance on the pond, but I was able to capture closer images of the same species on the 29th on Galveston Island, below. Breeding adults have chestnut plumage glossed with green or purple. All plumages have a powder blue line on the face that does not completely encircle the eye, detail in 4th frame below. (Reference: National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, 7th Edition, Dunn and Alderfer, p 266.) This bird is preening, showing long legs and decurved bill. Eye detail below. White Ibis, first springAbove, on Shoveler Pond, is a White Ibis in the first spring. The adult is white with a pink/red face and white eye. The juvenile has a dark eye and dark back, but as it matures, in the first spring, distinctive white feathers come into the back with a mottled neck (Reference: National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, 7th Edition, p. 266) Both Glossy and White Ibises have similar foraging habits, using their long bills to probe for fish and crustaceans in the mud. Their range is similar, coastal marshes and wetlands of the southeast U.S with Glossy Ibises going up into New England, and White Ibises into Mexico. King RailAs we got closer to Shoveler Pond, we spotted two photographers with some serious telephoto gear intent on the edge of the reeds. We joined them and over time spotted a King Rail in reasonable light looking for food along the water's edge. King Rails are in the Rallidae Family along with Sora, Gallinules, and Coots. The King Rail lives near fresh water marshes and swamps from Mexico into New England. Their population has been declining in recent years, most likely due to loss of habitat and pesticide use. They are on the 2014 State of the Birds Watch List as being threatened or endangered without conservation efforts. This rail is 12 to 14 inches in length. Although there are no yardsticks in the wild, we do see the bird adjacent to a tree stump that is probably 4 to 5 inches in diameter. King Rails eat crustaceans, especially crayfish, as well as aquatic insects, and small fish. Virginia RailWe stopped at Brazos Bend State Park on April 30th, the last morning of our trip. This Virginia Rail was foraging among the reeds in reasonable light. Unlike the King Rail, the Virginia Rail lives throughout North America, wintering in the southern U.S. and Mexico and breeding north centrally all the way up into Canada. This rail is smaller than the King Rail, and has grey cheeks, a reddish bill, and cinnamon neck. It is said to be larger than a Sora, and smaller than an American Coot. We get an estimate of this bird's size from these images, where we can compare the size of the bird to adjacent reeds and stumps. Ohhhh, don't forget the Alligators !There are lots of American Alligators throughout the freshwater wetlands of SE Texas, and Shoveler Pond is no exception. Above, an American Alligator waiting for lunch to arrive. Below, an exercise in image recognition. Let's see, from top to bottom: log, log, . . log-log. . . . .log, log, . . . . sea weed. . . . . loooo . . . nooooo....ALLIGATOR! They do look like floating wood. The portions of head and back that show above water belie their full size. Below, an American Allligator out of the water getting some Texas sun. Below, a close up. Imagine just the nose, eyes, and top of back above water. There is a lot of alligator below water, with a big mouth, and massive jaws and teeth. Definitely no swimming in Shoveler Pond, and best not to fall into the water! That's it for Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. More posts soon. Happy trails! This is the next of an occasional series on birding the Texas coast in April, 2019. The first post was May 8th on the rookery at Smith Oaks, on High Island Texas. Today we move a bit south and west to Rollover Pass, Galveston Bay, map below. All the images here were captured at the little yellow dot at the bottom left of the map below. High island is the slightly greener elevation to the right on the map. The map is a feature of Adobe Photoshop Lightroom Classic CC that maps any images with GPS coordinates stamped on the file. Fortunately the Canon 7D Mark II has a GPS chip, which when combined with LR allows mapping of all my bird images, very helpful when trying to figure out "where were we?" when a photo was taken. Among the many shorebirds at Rollover Pass on April 28th was a Reddish Egret, dark morph, in full breeding plumage. The Reddish Egret is a medium to large heron that inhabits shallow salt water, and runs, jumps, and spins to stir up small fish during feeding. This species comes in light and dark morphs, and here we see the dark morph in full breeding plumage. Considered uncommon, this bird lives in shallow salt ponds and marshes in southern areas on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. The characteristic feeding behavior consists of spreading the wings and spinning and lunging over the shallows to stir up prey. The behavior is so specific that it can be used as a bird identifier when spotting the bird from a distance. On the 28th my subject was right in front of me, in good light, and "danced" a number of sets. Here are three that I was able to pull out of the deck of images. Set 1Without interruption, here is Set 1. Note in the last frame a small fish has jumped out of the water to the right. Set 2Here we see in the first frame a fish jumping completely out of the water, then splashing back in in the next frame. Set 3Third and last set. For more on the Reddish Egret see the Audubon Guide to North American Birds online. That's all for now! Happy trails! "Yup, best little rookery in Texas . . . " Pair of Roseate Spoonbills, Smith Oaks Rookery, High Island, Texas, April 26, 2019. The last week of April we traveled to Houston Texas and birded the Big Thicket and Texas Coast with Naturalist Journeys, led by Robert Behrstock and Robert Gallardo. We were joined by 8 other birders, and had a great trip and a great adventure. It is impossible to blog about the whole trip, but in coming weeks I hope to hit some high points, starting with the Smith Oaks Rookery on High Island, Texas. Rookery viewed from one of the elevated viewing structures at Smith Oaks. High Island Texas is situated on a tall salt dome on Bolivar Peninsula, to the east of Galveston. It rises 38 feet above sea level making it the highest point on the Gulf of Mexico between Mobile, Alabama, and the Yucatan Peninsula. A popular area to settle in the 19th century, it became an oil producing area from the 1930's until the 1980's [Ref: Texas State Historical Association]. More recently the Houston Audubon Society has obtained land from private residents and oil producers, creating four sanctuaries, the two largest being Boy Scout Woods and Smith Oaks, the latter including a rookery. The rookery at Smith Oaks is in Claybottom Pond, which was obtained from Amoco in 1994. In prior years industrial use had left an island in the middle of the pond which now suits itself perfectly for the rookery. By the mid 1990's herons were nesting on the island and then Roseate Spoonbills. By 2003 there were over 1000 nesting pairs at the rookery, including Great Egrets, Snowy and Cattle Egrets, Little Blue and Tricolored Herons, White Ibis, Neotropic Cormorants and Spoonbills. [Ref: Houston Audubon Society] The edge of the pond that is accessible to visitors has a series of two story viewing platforms making it easy to view and photograph nesting families up close. See photo above. Let's look at three birds that I captured on the 26th. Great EgretGreat Egret and chicks. Note the single Roseate Spoonbill just below the nest. They seem to prefer breeding close to each other. Great Egrets are stately white waders of southeastern coastal shores, ponds, marshes and mudflats. (They are winter residents in SE Arizona, where you can see them in prior blog posts.) Nesting pairs were in abundance at the rookery in April. Above, a parent with what appears to be three hatchlings. Both parents feed the offspring by regurgitating the adult diet which is predominantly fish. Below, the Great Egret nest crowded in among other species and breeders, including a Roseate Spoonbill. This is the preferred environment for these birds, with the Egrets building sturdy stick nests 10 to 40 feet above the ground. The island is ideal for nesting, being free of predatory mammals. However, the pond itself it full of alligators, and woe to the random chick that falls into the water. Great Egrets feed by regurgitation. In the sequence below we see two large fledglings ("When are those kids going to leave home!") aggressively looking for food from the parent, and competing with the sibling as well. One fledgling grabs the parent before any feeding can even begin. The sibling piles on. And you think dinner at your house is tough! It is not clear whether any feeding actually occurred during this sequence. Below it looks like the parent's eyes are in peril. The scrum continues. Finally some relief with vision intact. Hopefully the other parent is on the way with a crop full of fish. Neotropic CormorantCormorants are thin diving birds with feathers specially adapted to absorb water, becoming wet and heavy, facilitating the dive underwater for prey, predominantly fish. The birds cannot fly until their feathers are dry, so Cormorants are often seen in coastal areas or near ponds sitting on a rock with their wings outstretched, drying in the wind. The birds we see here are Neotropic Cormorants, the same species that is common on ponds in Tucson. Cormorants are social birds, and are often seen together, here nesting. At the rookery they will nest as a group, above, or close to other birds, below. Below, a pair of Neotropic Cormorants at their nest with chicks. Cormorants feed their young with regurgitated food. Given their ability to swallow fish head first, they "swallow" their offspring's head, so it can feed off of food in the parents crop. Offspring are fed by both parents. Here we see a feeding sequence begin. The chick ventures into the parent's mouth, and seems to completely disappear. Above, the whole head in in Mom's (or Dad's) throat, and the chick is feeding from the crop. Below, the chick comes up for air. On the left, we can see the other parent feeding another chick. If you are swallowing fish and frogs all day, head first, this looks easy. Certainly less hassle than the Great Egret feed, which looked more like a WWF match than a family meal. Roseate SpoonbillRoseate Spoonbills are in the same family (Threskiornithidae) as Ibises, and like Ibises they probe in the muck or feel about in water for their food. Of the 6 species of Spoonbill in the world, the Roseate Spoonbill is the only one that lives in the U.S., inhabiting the shallow coastal waters of Texas, east to Florida. They eat small fish and aquatic invertebrates by sweeping their flat bills back and forth in the water. They get their pink coloration from carotenoids in the food they eat. Their bright coloration and spoonbill make them look more suited for animation on the big screen than foraging in coastal waters. The spoonbills at the rookery seemed to still be in nest building stage. Eggs or chicks were not in evidence. Spoonbills are definitely awkward standing, but elegant in flight. Below are three images I grabbed on April 27th as a Roseate Spoonbill flew over Anahuac Wildlife Refuge, just north and west of High Island. References:

That's all for now! More on the Texas coast soon. Happy trails! |

AuthorHenry Johnson, photographer and author of this site. For more detail, see About

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed