|

Anhinga, Brazos Bend State Park, April 2019. The Bolivar Ferry to Galveston . . . . . .Magnificent FrigatebirdOn Monday April 29th we drove the vans onto the Bolivar Ferry to Galveston. As I got out of the van, I had the option of leaving my camera in the van, or lugging it up the companionway to the upper deck where everyone was congregating. Being a proponent of "never leave your camera behind," I took it with me - that really great shot was never captured by a camera left at home or locked up in a car. I hung out in the stern and grabbed some really bad photos of Laughing Gulls looking for food in the wake, when someone on the starboard side yelled, "Magnificent Frigatebird!" I walked around to the starboard rail, and sure enough, there was a frigatebird. See images above and below. Magnificent Frigatebirds have a deeply forked tail, and pointed wings. Here we see a female with a dark head and a white breast patch. The males have red gular sac (throat) most visible in the breeding season. They are known for aerobatics, catching their food in flight, commonly flying fish just above the water. The Magnificent Frigatebird, along with its cousin the Great Frigatebird, are in the Frigatebird Family, sharing the order Suliformes with the Boobies and Gannets, Anhingas, and the Cormonants and Shags. Unlike Cormorants, the Magnificent Frigatebird is most at home in the air, and does not sit on the water or swim. They breed in coastal areas of the southern U.S., Mexico, Central and South America including the Galapagos Islands. It was fun to see this bird in the channel. And, yes, I was glad I lugged my camera around the ferry! Galveston Island: Seaside SparrowOn Galveston Island we spotted this Seaside Sparrow in the grasses. The Seaside Sparrow is a habitat specialist of salt and brackish marshes. Occurring in relatively small, localized populations along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States, this species has been divided into several morphologically distinct subspecies. They nest in marshes with expanses of medium-high cordgrass with a turf of clumped, residual stems. Especially suitable are spots not subject to extreme flooding that have open muddy areas for feeding. Nest mortality is due to storm flooding as well as predation. (Ref: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology). As a maritime wetland specialist, the Seaside Sparrow is a potentially valuable “indicator” of ecological integrity of certain types of coastal marshes and has already proven sensitive to habitat modification in Florida. (Ref: Birds of North America, Cornell Lab of Ornithology). Brazos Bend State Park: AnhingaBrazos Bend State Park is on the Brazos River, about one hour drive from Houston. It offers recreational facilities as well as ponds and marshes for wildlife, with elevated walkways for viewing. This Anhinga was perched in a tree preening, then took flight. The morning was overcast, not uncommon for this trip, but the sun did come through long enough to provide some good light for these images. The Anhinga is a striking bird, with a long s-shaped neck, dagger-like bill, and fanlike tail. An aquatic species, it spends its life in water or on branches overhanging protected, usually freshwater streams and ponds. They have fully wettable plumage and dense bones, allowing them to stalk and spear fish while staying partially submerged in the water. Like cormorants, they need to dry their wings in the sun. The male Anhinga took flight. It appears that he is missing one primary flight feather on the right. Note the distinctive tail, which has been compared to the tails of turkeys. Little Blue HeronStalking the marsh at Brazos Bend was a Little Blue Heron, a small heron decked out in moody blues and purples. They live in the marshes and estuaries of the Southeast, eating small fish and amphibians. Here we see their slow methodological approach to hunting. Last frame show success, a crawdad for breakfast! Little Blue Herons build stick nests in trees alongside other colonial waterbirds. In the U.S., their populations have been in a gradual decline since the mid-twentieth century. Little Blue Herons may gain a survival advantage by wearing white during their first year of life. Immature birds are likelier than their blue elders to be tolerated by Snowy Egrets—and in the egrets’ company, they catch more fish. Mingling in mixed-species flocks of white herons, immature Little Blue Herons probably also acquire extra protection against predators. Below a series of images of an immature bird in fight. Note: In the first, third and fourth frames above we can see the alula, two feathers projecting from the edge of the wing. This is the bird's equivalent of the human thumb, sometimes referred to as the bastard wing. It is deployed in flight much like an airplane deploys slats on the forward wing, to deflect airflow over the wing itself to increase lift, especially at slow speed and when the wing is angled up to slow flight. The alula, like slats on a plane, prevent stalling at slow speeds. Without it, birds would either have to land at faster speeds, or would stall, suddenly dropping to the ground when landing. For more images of the alula, see my post on the American Kestrel at Ft Lowell Park, New Year's Day 2018. Purple GallinuleThe Purple Gallinule is among the most gaudy breeding birds in North America. Richly colored with deep blue, green, and purple and trimmed with red, yellow, and sky blue, this fresh-water wetland species has proven adaptable to habitat modification, thriving in natural as well as human-made plantations and refuges. It lives in marshlands in the southeast U.S. as well as coastal Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, eating a variety of foods including flowers and fruits of the water-lily family, as well as invasive exotic plants and rice. Although primarily plant eaters, they also eat spiders, mollusks, beetles, bees, worms, snails, dragonflies, leeches, ants, grasshoppers, and moth larvae, as well as frogs, small fish, and eggs and nestlings of other birds. (Ref: All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology). Here we see a Purple Gallinule taking long strides through the marsh looking for food. Their long toes are well suited for either marsh walking or clinging to vegetation.

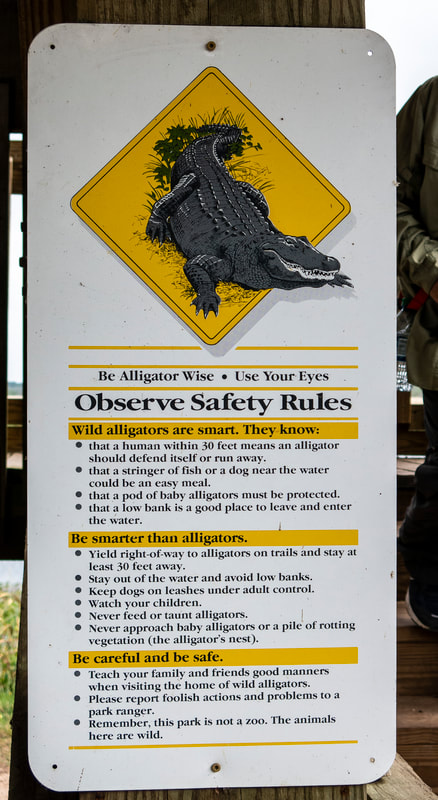

American Alligators, once headed for extinction, are now in abundance in rivers, lakes, swamps and marshes of the southeastern U.S. We saw them throughout SE Texas on this trip, wherever there was fresh water. Heavy and ungainly out of water, these reptiles are supremely well adapted swimmers. Males average 10 to 15 feet in length and can weigh 1,000 pounds. Females grow to a maximum of about 9.8 feet. They feed mainly on fish, turtles, snakes, and small mammals. However, a hungry alligator will eat just about anything, including carrion, pets and, in rare instances, humans. [Ref: National Geographic] The alligators at Brazos Bend are very close to the pathways, and often will walk across them, or sun themselves on a path. The park has many posted warning signs, one of them above. Below, an alligator at Brazos Bend. For more alligator images, see this posting on Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. This is the last post, Part V of V, on the Texas trip! I want to express my concern for all those in east Texas affected by the recent flooding from tropical storm Imelda. During our trip in April we stayed two nights in Winnie, and traveled in and out of areas that were completely covered with water from this recent storm. Brazos Bend State park likely flooded as well. The American Red Cross is active in east Texas, and provided temporary shelter for many. If you would like to contribute for aid to those affected by the flood, go to this link for the American Red Cross. Thank you! Happy Trails!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHenry Johnson, photographer and author of this site. For more detail, see About

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed