|

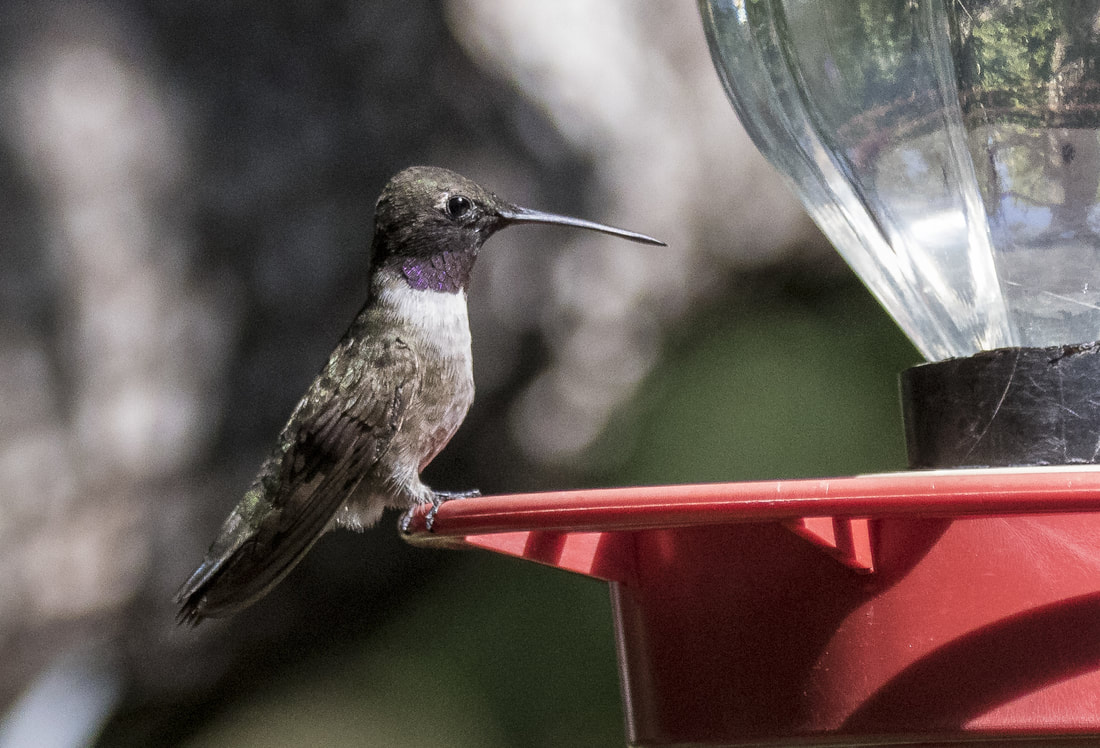

August 10th to the 13th Tucson Audubon hosted their annual SE Arizona Birding Festival, based at the Arizona Riverpark Inn on Cushing Street close to the Tucson Convention Center and I-10. Friday the 10th we loaded onto a van and toured south to Patagonia with Richard Fray. Saturday the 11th I signed up for the photo workshop at Madera Canyon with special guest, author and photographer Paul Bannick, and Sunday we went Humming-birding with Karen Krebbs. The photo workshop in Madera Canyon was excellent, but short on birds, so this post will focus on our Friday and Sunday adventures. Five-striped SparrowFriday, 8 of us left in a van at 5:30 am led by expert guide Richard Fray (see his website) to selected birding hotspots in Montosa Canyon and then near the San Pedro River near Tumacacori. We finished at the Paton Center in Patagonia for lunch and Hummingbirds. The Five-Striped Sparrow had been spotted in Montosa Canyon, and sure enough, we spotted him in the early light of this spectacular canyon. Fortunately he decided to sit and sing on a branch as the sun filled the canyon from the east, and I got these shots. So, what's so special about the Five-striped Sparrow? Well, it is endemic to western Mexico, and crosses into SE Arizona occasionally. It can be found in rocky canyons adjacent to streams and low dense growth of mesquite, acacia, and hackberry with taller stands of ocotillo. (Reference: Audubon Guide to North American Birds). So, for birders keeping a life list of birds spotted in the United States, or maybe even doing a BIG YEAR, finding a Five-striped Sparrow is a big deal. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology Neotropical Bird site has a good summary of this bird. "It is typically observed alone or in pairs, in arid to semi-arid scrubby country, often in rocky areas, and it is easily overlooked, except when singing. The Five-striped Sparrow is a neatly patterned sparrow, with brown upperparts and principally gray below, but marked by a white supercilium, throat, and moustachial, and a broad black malar stripe; there is also a small black spot on the breast. The species resident in some areas, but most populations move south in winter, albeit not over very long distances." Rose-throated BecardThe Rose-throated Becard is common in Mexico and Central America, but rarely comes as far north as SE Arizona, or S. Texas, and thus is considered scarce in the U. S. The Audubon field guide describes their habitat as: "Wooded canyons, river groves, [and] sycamores. In Arizona, usually along streams at middle elevations, especially in groves of sycamores and cottonwoods; sometimes in pure cottonwood groves with understory of mesquites. In Texas, generally in native woodland near Rio Grande. In Mexico and Central America, widespread in dry woods, canyons, locally up into mountain forest." As individual birds, they are tough to spot. Often the first indication of their presence is their large tangled hanging nest. Richard led us to a nest along the Santa Cruz River near Tumacacori not far from the Anza Trail. Below, an image of the nest with the female sitting to the right. This male was elusive and difficult to photograph. He stayed high in the trees, behind leaves and often in the shadows. Below he is hanging onto a branch sideways. The Rose-throated Becard eats insects and berries, mostly the former during the summer breeding season. They sit high up in Sycamores and Cottonwoods, catching insects and returning to their perch. For more on the Rose-throated Becard see the Cornell website on Neotropical Birds. Gray HawkWe were cruising along in our 10 passenger van, listening to a running commentary from Richard, when he suddenly pulls over to the side of the road, just beyond a wash and a one lane bridge. "Gray Hawk," he cries, and we all pile out and walk back to the wash, avoiding the bridge, which is too narrow for cars and birders. Yes, a Gray Hawk in the distance on a telephone pole. [Question: where did they perch before electrification of the southwest?]. Gray Hawks are in the genus Buteo, sharing the genus characteristics of being thick-set, with broad wings and a wide rounded tail. The Cornell website says it well: "A tropical species that barely crosses the border into Arizona and Texas, the Gray Hawk is an elegant, raincloud-gray raptor with neatly barred underparts. They spend their days gracefully soaring over open areas or perched in cottonwoods, willows, and mesquites along lowland streams. They patiently watch for lizards, then catch them with a swift dart toward the ground. Gray Hawks are small for a hawk in the genus Buteo, and their longish tails and flap-and-glide flight style can make them resemble accipiters." The banded black and white tail is evident in these images. And, he took off! Here we can see the banded tail, and the finely striped gray and white flight feathers. Rufous Hummingbird and friends . . .A quick shift to Sunday August 13th. Another early morning departure in a Ten-passenger van on a Hummingbird Safari led by Karen Krebbs. After a sunrise drive south to Sierra Vista, and a welcome stop for coffee, we continued south to Miller Canyon in the Huachuca Mountains, and the Beatty's Guest Ranch and Orchard. See their website for more information on lodging, birding, and their orchard. We were warmly greeted and led up past the orchard and across a creek to the side of the canyon and a set of bleacher seats overlooking a raft of feeders, all numbered for better communication. The trio above features a Rufous Hummingbird on the left, and on the right a noticeably larger Rivoli's Hummingbird (until 2017 known as the Magnificent Hummingbird), and in the middle likely a male Black-chinned. The Rufous Hummingbird is a brightly colored, feisty fellow we see in Arizona as a migrant, stopping in mountain valleys to feed during an annual journey that takes him on a clockwise circuit from winters in Mexico up the Pacific Coast to southern Alaska to breed, then all the way back again by way of the Rockies. Check out the range map on the Cornell site here. Below is another view of the Rufous Hummingbird, showing more of the characteristic coloration. Rivoli's Hummingbird, the bird formerly knows as Magnificent, is among the largest of hummingbirds, which we can see in the first image. Like many of the species we have spotted during the festival, they winter in southern Mexico and Central America, and breed in northern Mexico, just coming over the border into the U.S. during the summer. Again, rare in the U.S. and only in summer in SE Arizona. In addition to their large size, the male is distinguished by an iridescent purple crown, green throat, and black belly, as we can see from the two images below. Black-chinned Hummingbirds are widespread throughout the west. They have a green back, a black chin with a white collar, and a iridescent purple band at the base of the chin, which varies in intensity depending on the angle of the light, as we can see in the views below.  Above, Black-chinned Hummingbird Lucifer HummingbirdWe left the Beatty's ranch, stopped by the road for lunch, and then headed south on Hwy 92 to the Ash-Canyon Bed and Breakfast. Mary Jo Ballator has run this combination of B and B and birding hotspot for some years, and has great reviews on her website. There is a fee for birding during the day, and rules for photography, with an additional fee for use of a tripod. If you plan on going, review her website in advance. Mary Jo has two areas of her yard set up with feeders, and an abundance of birds, including species that are rare in the U.S., but more common in her yard given her proximity to the border. It is here that we spotted a Lucifer Hummingbird returning to one feeder repeatedly, making it easier to capture images. The Lucifer is a small hummingbird with a decurved bill. The male, image below, has a purple throat with buffy sides, and no purple on the crown. The tail is deeply forked, as we will see in later images. (Reference: Peterson Field Guide to Birds 2010). The Lucifer likes Agave flowers, and will also come to feeders, but is often chased off by other hummingbirds. To accommodate to their lower pecking order, Mary Jo has specially set up individual feeders, as shown above. This male returned repeatedly to this feeder, and avoided the circular "gang feeders" that other hummers were using. Two images below show the same bird, at different angles. The decurved bill is clear. The Lucifer Hummingbird has a forked tail, which was not evident when hovering at the feeder, but did open up as he moved away. Below are two images showing the forked tail. The Lucifer winters in southern Mexico and into Central America, breeding in northern Mexico and just into the U.S. in SE Arizona. The Huachuca mountains are a hot spot for them in U.S. For more information, see the Cornell website. Closing with an old friend, the Northern CardinalGosh, sometimes all these rare birds can just get exhausting! So let's close with the Northern Cardinal, photographed at the Paton Center in Patagonia at the end of Richard Fray's tour on Friday. Of interest is the scruffy "punk" look to this male, likely the result of moulting in August. My guess is that this male lost his crown entirely, and is now slowly growing it out. He dared to peek out at us, and we promised not to laugh. We know he will be looking much better soon! In Closing . . . .Many of the birds we saw on our tours we, birders in the U.S., consider Scarce or Rare. This is not because they are truly scarce but rather because they fly a map without borders. They have no idea which country, county, or village they are in. They want to eat and reproduce. Many of them live south of us most of the year, only venturing across the border into the U.S. in the summer.

I wonder if the Rose-throated Becards get together at night over fresh bugs and chat: "Did you see all those birders today? I told you we were nesting too far north . . ." Happy trails!

1 Comment

|

AuthorHenry Johnson, photographer and author of this site. For more detail, see About

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed