|

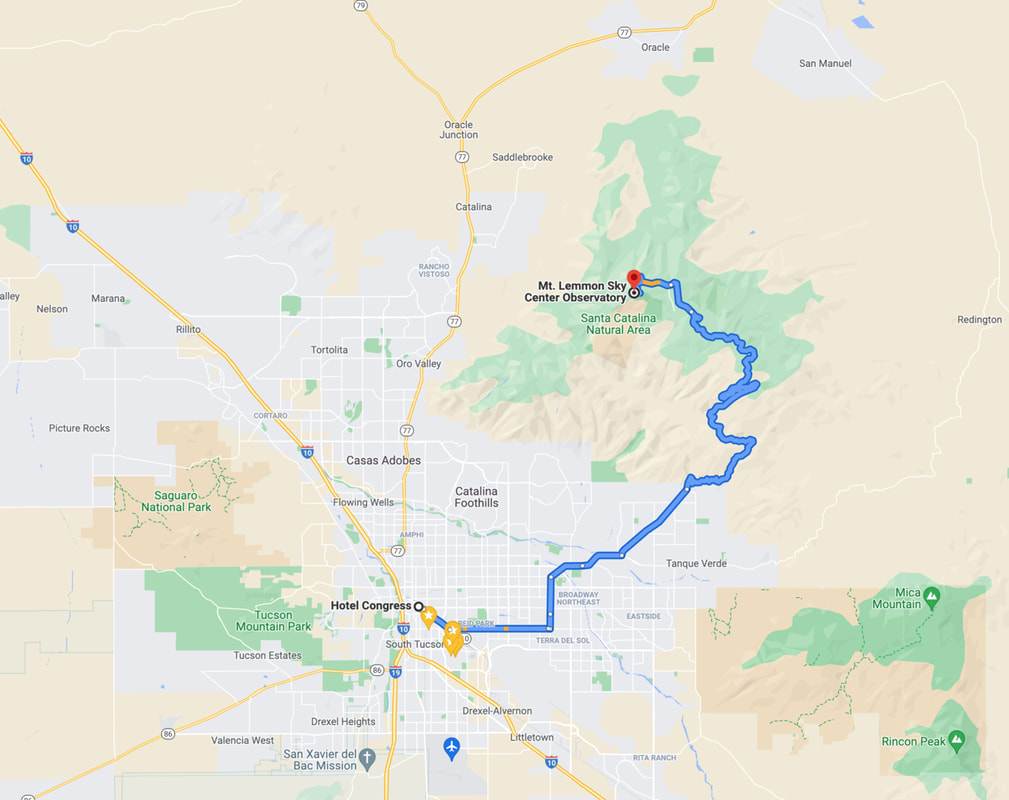

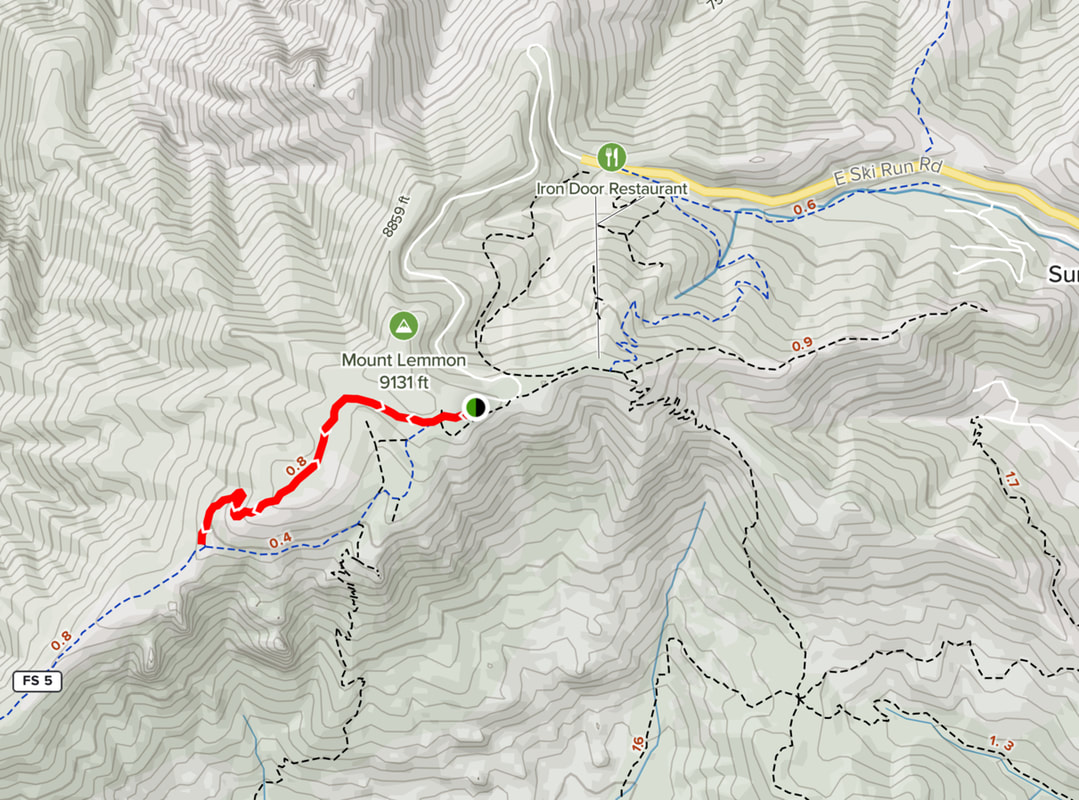

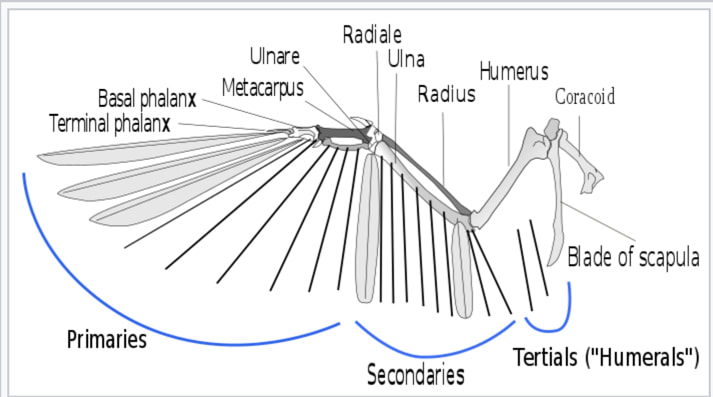

White-breasted Nuthatch, August 30, 2021, Mt. Lemmon, AZ, ~9000 feet altitude. I know that some readers have not been to Tucson, or Mt. Lemmon, so below is a Google map for orientation. I asked Google to plot the route from the Hotel Congress in downtown Tucson near the train depot and Interstate 10 to the University of Arizona Sky Center Observatory at the top of the mountain. The map below shows the route across Tucson, through the Tanque Verde Valley, and up the General Hitchcock highway to the top of the mountain. From downtown, it is about a 90 minute drive, going from from 2500' up to the top of the mountain at 9000'. (The rest of this website has a lot of content on Mt. Lemmon and Summerhaven, see the Home Page) For more on Sky Islands in Arizona, see this link. The map below shows the route of the Meadow Trail, which begins in the parking lot at the observatory gate. The trail runs just south of the observatory, and then opens up to a beautiful high meadow. It continues downhill on the north side of the mountain and connects to a forest service road that goes either downhill, or back up to the parking lot. The photograph below is the best in my archive, captured in 2019, showing the expansive beauty of this meadow. It is relatively flat at the top and high at 9000'. The trail runs east to west, passing the edge of the summit, looking out over the southern part of the range and Tucson below. The photograph below is at the rocky edge facing west and south, with Pusch Ridge in the mid-ground and Davis-Monthan Airbase in the valley to the left. (For the photo geeks: I went out this day with my Canon RF 100-500mm on a R6 body, and no other lenses or cameras, except my iPhone. The image below is two images from my iPhone imported into Lightroom CC as jpegs, and put together into one panoramic image, with edges filled in with LR's Fill Edges option, which works really well. When out on the trail, don't forget that your phone has a good camera in it!) The image below is shot from the same location as above, but facing east and south. The terrain drops off pretty quickly to the south, allowing good views of the Tanque Verde Valley and the Santa Rita Mountains to the south. And, you may see soaring raptors, often "eye to eye." Which brings us to the Red-tailed Hawk. Red-tailed Hawk in the Sky over TucsonOn a very windy Sunday in August, several Red-tailed Hawks were soaring close to the rocks, just south of the meadow. One of the hawks hung around for a while, and I was able to get this sequence. In the images above and below, the hawk is actually below me off of the rocks, so I am looking down on him/her, not the usual view we get looking up from the desert floor. The Red-tailed Hawk has a stout body and broad wings, with a short, wide, reddish tail. Most Red-tails are dark above, and pale below with a streaks on the belly (often with the appearance of a dark band), and on the underside of the wing a dark bar between the shoulder and wrist. The two sexes have similar appearances. They live throughout North America, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, with breeding territories up into Canada and Alaska. Plumage color and pattern can vary widely in different populations with broad categories of light or dark morphs. The dark-morph birds are all chocolate-brown with a warm red tail. Rufous morph are reddish-brown on the chest with a dark belly. The bird we see here likely has the usual coloration for our area, with the paler underside. My subject was working hard to stay stable in the stiff wind, with his legs lowered, I suspect to stabilize his flight. He wheeled around, and I caught this sequence. Above we see the bulk of his body from the rear. He looks like a loaf of bread with wings. What we can see of the underside is pale. He begins to move to the east on the wind, and looks back toward the ridge, likely looking for food, or defending territory. Red-tails in SE Arizona likely live here year round, and will defend their territory. I have seen territorial disputes in the skies over Summerhaven. For more see my post of October 2019. (Reference: Birds of the World). At 9000', we can see the hawk below us with the homes of the Tanque Verde Valley as background. For completeness, I am including images of Red-tails from different locations and dates so we can see markings and morphs better. Below is Red-tail with "standard" markings, dark back, pale underside and a band across the belly, perched looking for food at Sweetwater Wetlands in November of 2017. The same hawk taking off, image below, showing markings under the wings. Below is a Rufous Morph, in flight over Summerhaven in the fall of 2019. This hawk was the victor in an aerial territorial dispute with another Red-tail. We can see the reddish markings under the wings. For the photo geeks: Most shots of raptors are from below, and the underside of the wing is almost always in shadow, except for early or late in the day when the sun is low in the sky. In post production I can lighten the shadows to see better details, but there are limits. Too much manipulation and the photograph does not look right. Below is the same bird perched in a nearby tree . The rufous marking on the chest and belly are clearly different from the hawk photographed at Sweetwater Wetlands in 2017. One more morph to go, the Light Morph, seen in the image below in flight at the Wilcox Lake/Golf course in May of 2018. This is a juvenile, likely in the second pre-basic molt, evident with the wings fully extended. (Reference: Birds of the World) The Red-tail has 10 primary flight feathers and 14-16 secondaries (for anatomy, see the diagram that follows). The molt progresses over weeks beginning with the junction of the primary and secondaries and working outward on the primaries and inward on the secondaries. As one feather comes out, a new one comes in. The feather loss and regrowth is symmetrical, and timed so that only a few feathers on the wing are regrowing at one time. This allows the raptor to continue to be the "ultimate hunting machine" while these vital structures get replaced. In the image above we can see the molt in progress on the flight feathers, as well as the tail, where the molt begins in the midline and progresses outward. Note that the new tail feathers are redder than the old ones, consistent with the bird's age and molt. In the image below we can see that the dorsal surface of the tail is red. I have included the diagram shown below from the Wikipedia page on Bird Wings to show the primary and secondary feather locations and their relationship to the bones of the wings. The bird wing is remarkably similar to the human arm. In birds, the humerus is relatively short, with a longer ulna and radius. The secondary flight feathers are attached to the ulna, the primary flight feathers are attached to the partially fused "hand" bones. The joint that allows so much movement of the primaries (folding, extension, flight control) is the equivalent of our wrist. The avian "thumb" is the known as the Alula (or "bastard thumb"). It is shown as a small bone in the diagram above and we can see it with associated feathers in the image below, an American Kestrel diving for prey on New Year's day 2018 at Ft. Lowell Park. The alulas function like the slats on an airplane, disrupting airflow and increasing lift at lower speeds, helping to prevent stalls as birds land. This is especially important for raptors. Special thanks to Jeff Babson for his help in verifying species and morphs for this section. Next, 2 Nests in the Meadow, 1 on the TrailI was able to photograph three nests this summer on or near the trail #1 Plumbeous Vireo Nest in the MeadowThe Plumbeous Vireo is a lead-gray songbird with bold white spectacles; eye rings "attached" by a white bridge across the nose. For more on this species and its family click here. Plumbeous Vireos winter in southern Mexico and Central America, and breed in the mountains of Mexico into SE Arizona and north into Utah, Nevada and Colorado. A pair of Plumbeous Vireos built a nest in the summer of 2021 in the meadow, not far off the trail, about 6 feet off of the ground in pine branches that had been scorched in the Bighorn Fire in 2020. In this series of images, we can see the hatchlings being fed by both the mother and father. The sexes look alike, so I cannot tell which is which, although I saw them both at the nest at the same time. The male selects the nest site, generally at forked branches, and the female does the building. For the photo geeks: I shot this series with a Canon R6 and a Canon EF 100-400mm Mk II with 1.4 Mk III extender, on a tripod. I was stopped down to f/11 to improve sharpness at 1/1000 second, with ISO's in the 4000 range. Nests are typically in dark locations, and in this case I traded off a fast shutter and smaller aperture for a higher ISO. I tried to be as non-invasive as possible. When shooting a nest, if it looks like I am interfering with feeding or disturbing the parents, I will retreat. Be careful about sharing nest locations to avoid nests being overrun by birders and photographers. Large numbers of individuals, even with the best intent, can be quite disruptive. #2 Violet-green SwallowsBefore we get to the swallow's nest, let's go back to my post of June 2020 when I showed images of this Violet-green Swallow perched and preening in between aerial sallies for insects. Violet-green Swallows winter in southern Mexico and Central America, and breed from northern Mexico into Alaska. Mt Lemmon is in the southern range of their summer territory, with open skies and lots of bugs to the south of the rock ledge, and lots of nesting locations in the woods to the north. These birds move very fast and dart quickly, making flight photography a challenge. This series was captured in May of 2020. In the image directly below, I suspect this is a male calling as part of the spring mating routine. Below, the wings when folded are longer than the tail. We can also see the violet rump. Like other cavity nesting species, Violet-green Swallows often have more parasites on their feathers than other birds. To control the parasites they sunbathe and preen frequently, as we can see in this sequence (reference, All About Birds). Fast forward a year to July 11, 2021, when a birding buddy of ours, Marty Herde, spotted this cavity nest (image below) high in a dead pine tree. This is a typical location for Violet-green Swallows. This was a solitary nest, although this gregarious species may nest in small colonies of up to 25 pairs in open woodlands. Males and females build the nests together as a shallow cup at the bottom of a cavity in trees, cliffs, or in nest boxes. The clutch size is 4-6 eggs, with one or two broods in a season. Below we see what is likely a male coming in for a landing at the nest hole. I suspect it is a male because of the green cap, the females being drabber with a darker cap. Dad folds his wings back, then deploys them forward to brake and create a stall at just the right time to dive into the hole. In the image above we can see how long the wings are. Violet-green Swallow wings have a high aspect ratio, that is, the ratio of the length of the wing to the width. High aspect ratios produce lots of lift, with the pointed tip reducing drag while gliding. This makes extended flight and gliding more efficient, helpful for swallows who must get all their food while on the wing. Note also that this bird's feathers are a bit beaten up. A broken (absent) feather will be regrown, but normal wear and tear must wait until the next molt, likely this fall for these birds. In the images above and below we can see the violet rump as dad dives into the nest with lunch. The white belly wraps around to the upper side of the rump creating "saddlebags." For the photo geeks: These birds are among the fastest fliers I have seen; only hummingbirds in sprints seem quicker. The only way I could catch photographs of the parents coming and going was to place my Canon R6 with EF 100-400 lens and 1.4x Mk III extender (560 mm total) on a tripod and aim it at the nest hole, and fire it when a bird was close. I attached a radio controlled shutter release, and set the R6 to electronic shutter, silently capturing 20 frames/second. I stood away from the camera and when a parent got anywhere near the tree, I hit the shutter. I got hundreds of shots, mostly of the nest hole with no birds present, but I did get this series as the payoff. This whole sequence occurred in less than one second! #3, One by the trail, Momma Broadtail on her nest. . . . . .The final nest is that of a Broadtail Hummingbird very close to the trail, yet fortunately for the mother bird hard to see, as the trail makes a switchback downhill to the north. Again, my thanks to Marty Herde for spotting this. Although only 4 or 5 feet from the trail, it was hard to spot, and this female raised at least one hatchling to the fledgling stage. Building the nest, incubating the eggs and feeding the young is all done by the female; the male is only the donor of genetic information. The nests are made up of all local materials, including generous portions of spider webs that give the nest elastic properties. As the hatchlings grow, so does the nest. Imagine having a house made of spandex. No need to move as the family grows, everything expands to accommodate the kids. We know this is a Broadtail by the buffy flanks. Three Nuthatches fly into a Meadow . . . |

AuthorHenry Johnson, photographer and author of this site. For more detail, see About

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed