|

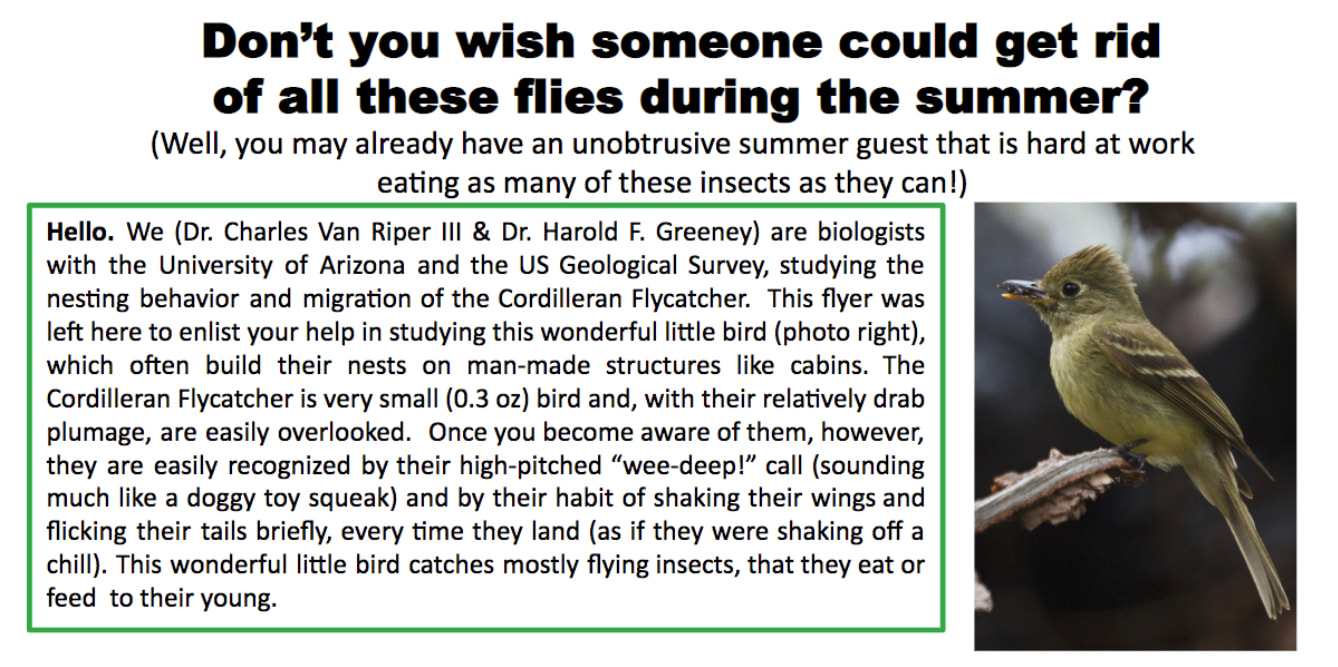

Cordilleran Flycatcher nest, Mt Lemmon, July 2019 Cordilleran FlycatchersI know it is October, but let's hang on to a bit of summer and look at some of the nesting activity of the season on Mt Lemmon. Remember, the name of this website is after all, Mt. Lemmon AZ Images. Let's start the Cordilleran Flycatcher, a small bird that winters in Mexico and breeds in mountain regions from Mexico to Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montano and Idaho, including the Catalina Mountains here in Arizona. It is closely related to, and almost indistinguishable from, the Pacific Slope Flycatcher, which breeds along the Pacific Coast at lower altitude. These two birds were once considered one species, the Western Flycatcher, until 1989, when they were split into their current species and names. Most of the research on these birds was done before the split, making knowledge of the Cordilleran Flycatcher sparse. If you were in Summerhaven this past spring, you may have found a flyer like this one on your car. In order to learn more about the Cordilleran Flycatcher, Drs. Charles Van Riper III and Harold Greeney have been working for a number of years studying their nesting and migratory behavior. Charles has summered in Colorado in past years studying Cordilleran nesting, but this year as a U of A biologist he moved his summer work to Mt Lemmon, joining Harold's data collecting activities. Drs. Charles Van Riper III and Harold F. Greeney, Mt Lemmon, July 2019. To study birds, one must be able to identify them as individuals. Since they don't share their names easily, it is best to stop them for a while and give them an ID bracelet. Or in other words, carefully capture them in a net and band them. Nesting parents often return to the same place to nest year after year, so banding allows researchers to track birds over years and determine their nesting habits. The photograph below is a female Cordilleran Flycatcher collecting nesting material along Sabino Creek, Turkey Run, Mt. Lemmon, July 2019. Below, likely the same female up close with nesting material. She was trying to build a nest on the rear bumper of Charles' truck (not successful!). Cordilleran Flycatchers are ledge nesters, and will build on almost any flat spot that looks good. To encourage nesting, Charles has designed a wooden nest box consisting of a covered ledge, open on two sides. The birds prefer the morning sun, so boxes are oriented with the open side toward the east and north. This box along Turkey Run was used by a female for nest construction, but she never used it as a nest. Below an image of a successful nest on a cabin roof beam. The chicks fledged a few days after these photos were taken. Below, you can see two hoses neatly hung ready for use behind a cabin. A successful nest was built on top of the further hose, hung under the deck, very well hidden from predators. Charles was able to net and band the parents and offspring. If they come back next year, he will be able to identify them. Below, a photograph of one of the parents of the nest above, successfully captured and ready for banding. Charles has spent his life doing this, and I estimate he has banded ~40,000 birds during his career. (He is really good at this!) Image below, Charles is applying a metal ID band. Females are banded on the left, males on the right, allowing for quick gender ID. Colored bands are placed on the opposite leg to allow Charles and Harold to identify banded birds in the field with binoculars. A series of measurements are taken including length of wing and tail components, leg and bill length as well as weight. For studies of migration, banding works well if there are a large number of people banding birds at multiple sites, such as the Hummingbird Monitoring Network. However, for small groups of researchers working in one or two sites, tracking birds geographically is difficult. A solution is to have the birds carry geotrackers, which will record where they travel. Charles has used geotrackers in his work in Colorado, and this summer placed them on adult breeding birds on Mt Lemmon. Pictured below is one of the devices, which has a battery and a solar panel, and records time, sunrise, sunset, and the position of the sun. The tracker, in the best of circumstances, will last a year, and if retrieved next summer, will have stored data that will show where the bird wintered and how he got there. The loops go over the legs with the tracker sitting like a fanny pack on the bird's equivalent of our hips. The tracker is light enough to not interfere with flight, or feeding. Pictured below is an adult with a tracker on. The device is visible between the wings, and if you look closely, you can make out the serial number. Cordilleran Flycatchers are ledge nesters, and almost any ledge will do. Pictured below are some nests built on Turkey Run this past spring. The successful ones are generally well hidden. The eggs or nestlings can be lost as food to predators, including ground animals or other birds, including Steller's Jays. The nest seen below is in a cavity at the end of a large downed tree. This site was very exposed, and did not succeed. Females will rebuild failed nests until it becomes too late in the season to complete the nesting cycle and migrate south. This female will try again next year. Below, we can see another female and another nesting spot, this time in a open spot on a dead tree. The next nest was built off of the beaten path in the base of a downed tree in what had been the root ball. A combination of root structure and soil make a good spot to build. This nest was successful. Although the female builds the nest and incubates the eggs, both parents feed the nestlings. This was a nest that Charles and Harold had identified and studied. My thanks to them for sharing the nest site with me and the opportunity to photograph the birds. What follows is a feeding sequence. These images were captured in a two hour period around noon on July 13, 2019 in the woods up Turkey Run. I mounted a Canon 7D Mk II with a 100-400 mm IS II lens with 1.4 III Extender on a tripod with a Wimberley gimbal mount. I attached a wireless remote shutter release, allowing me to set up the camera away from the nest and trigger it remotely as I watched activity around the nest. I think most of this feeding was done by the male. He would leave to gather food, then reappear, perching on branches above the nest. I quickly learned that he would perch above, swoop in, land on the nest and feed the nestlings very quickly, then pause to look around before he left. As soon as I saw him close to the nest I got ready, and when he flew toward the nest, I pressed the shutter release. The Canon 7D Mk II can shoot in bursts of 10 frames a second, ideal for this setting. There appear to be three nestlings. They fledged a few days after these images were captured. The next series shows a fecal sac transfer, the bird's equivalent of diaper duty. Nestlings for many species will "package" their solid and nitrogenous waste into a fecal sac, a little bundle of waste surrounded by a membrane. One of the parents will accept the sac and then fly off site to dispose of it. This keeps the nest clean and free of waste odors which might attract predators. Some parents will swallow the sac (eeeewww !!). The nestling's immature gut will not absorb all nutrients, leaving valuable protein and calories behind that the parent can use. Images above and below, the nestling moves his hindquarters toward the watchful parent. Next, the fecal sac is expressed. Dad grabs the fecal sac, and shows it off for the camera. (Yeah, I know, he's not really posing for the camera, but it looks that way!) Whoosh! Off and away! The kids will wait for the next take-out delivery. Many thanks to Charles and Harold for letting me into their research community this summer and for guiding me to nests I would not have otherwise discovered. American RobinThe American Robin lives throughout North America, including SE Arizona and Mt Lemmon. One of our neighbors on Turkey Run spotted this nest just off of their deck, and gave me a call. I set up my tripod on the deck, and got this series of images. I started mid-morning, which is still fairly dark in this valley. As the sun rose, it filtered through the trees providing better lighting on an intermittent basis. Above and below mom is sitting on her brood, which appears to be two birds, getting ready to fledge. Female Robins during breeding season will lose their feathers on their abdomens to create a bare brood patch which allows more efficient transfer of heat to her eggs and hatchlings. For the photo geeks out there, I used the same gear and set up as for the Cordilleran Flycatcher nest. Our thanks to the fire-wising crew who was getting ready to cut and haul away this downed branch, but paused when they saw the nest, and saved their trimming for later. Below, a feeding sequence. Both parents feed the young. These birds are banded, and my guess is that the female is feeding, with dad looking on. Looks like breakfast today is earthworms. Below are images of another feeding sequence, a bit later in the morning, with better light filtering through the trees. American Robins also express fecal sacs as we saw with the Cordilleran Flycatcher. If you are going to eat, you're going to poop! Below is a sequence with dad doing diaper duty. Note that birds have kidneys that excrete urine directly into the cloaca, the end of the large intestine, the equivalent of the human rectum. Here urine is modified to conserve water and balance electrolytes, and is then packaged with solid waste from the intestine for elimination. Thus the fecal sac is a combination of solid waste from the gut and nitrogenous waste from the kidneys. This bird, like the Cordilleran Flycatcher, has the ability to create a membrane around this bundle, but only as a nestling. Below, mom is back sittiing on the nestlings, who are getting big! Their wings are pushing out the sides of the nest, and also in mom's face! Below, one of the fledglings looks ready to leave. After the fledglings leave the nest, the parents will follow them as they stay close to the nest and continue to feed them for up to 3 weeks. If a female starts another nest, the male will continue to look after the first brood. That's it for nesting on the mountain! Have a wonderful fall. Happy Trails!

8 Comments

Donna pierce

10/3/2019 08:48:28 am

Henry, it was a pleasure seeing these photos and reading the stories behind them.

Reply

Mike Anderson

10/3/2019 09:12:08 am

Henry

Reply

Kenn Block

10/3/2019 11:03:16 am

I share my brothers info for bird people.

Reply

Steve Brigham

10/3/2019 02:39:26 pm

Henry - these were fabulous! Many thanks for putting together the sequences and wonderful annotations. I just installed a flycatcher nest platform but may need to reconsider the location based on your observations.

Reply

Henry Johnson

10/3/2019 10:30:41 pm

Thanks to all for the nice comments. Glad you enjoyed the post. Kenn: thanks for the link to your brother's blog - his photos are great! Happy October everyone!

Reply

Bernadette Blatt

10/5/2019 07:56:25 am

In August and September nearly 3 dozen people purchased nesting platforms for the Mt. Lemmon Cordilleran Flycatchers. Your wonderful photos and narrative will inspire them to hang the platforms and help them understand the activities they witness if a nesting pair chooses to make it their "summer home." Thanks, Henry, for teaching us so much and taking us deeper into the lives of birds on the mountain.

Reply

Virginia Zuelow

10/9/2019 09:05:02 pm

Wonderful photos and bird life history info.

Reply

2/13/2020 01:59:24 am

If you don’t have a charging pad around then you can charger it using a USB cable. The battery also has two outgoing wired socket.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHenry Johnson, photographer and author of this site. For more detail, see About

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed