|

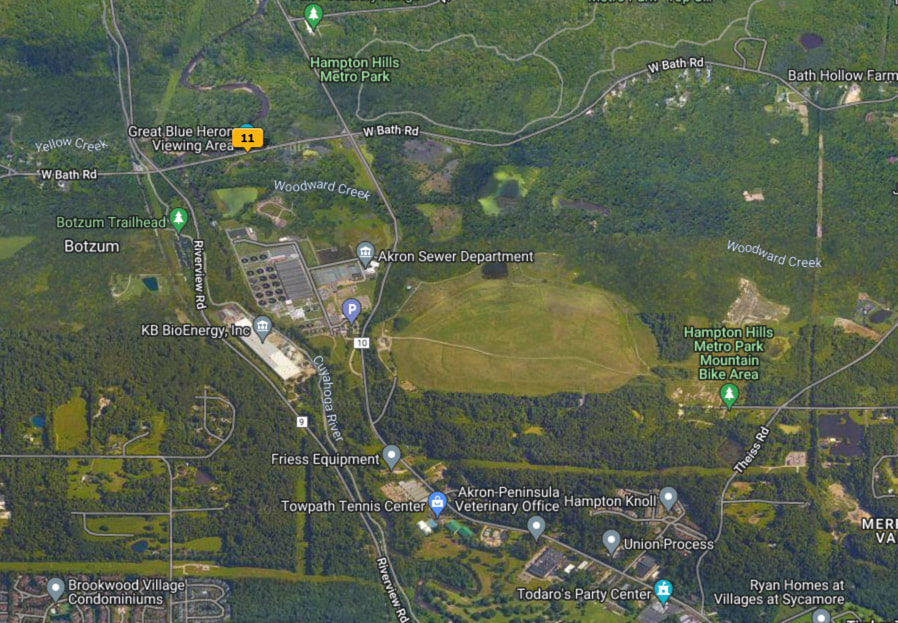

Nest in Great Blue Heron Rookery, Akron, Ohio, May 15, 2022. Purple MartinsCanon ESO R6 with RF 100-500mm with RF 1.4 extender at 420mm, 1/4000 sec, f/10, ISO 5000 Purple Martins are songbirds in the Swallow family, Hirundinidae, along with Tree Swallows, Violet-green Swallows, Bank Swallows, Barn Swallows, Cliff Swallows, Cave Swallows, and Northern Rough-winged Swallows. Purple Martins winter throughout central South America, migrating up through Central America and Mexico in the spring, breeding for the most part east of the Rockies from the gulf coast up into Canada, with some nesting in the mountains of Mexico and Arizona and along the U.S. Pacific Coast. Martins are cavity nesters, but have nested in houses beginning with native Americans hanging up empty gourds as nests well before European settlers arrived. In the early 19th century John James Audubon chose his lodgings based on the quality of the martin boxes hung on tavern sign boards. By 1900 almost all nests east of the Rockies were in human built habitat, whereas the western populations still nest in traditional tree cavities. Martin houses are generally arranged like condos or apartments in clusters, as shown in the image above. Here there appears to be 18 units on the pole, elevated well above ground level. The materials for houses vary, including the units we see here molded out of plastic to look like gourds, with screw-on side caps for cleaning, a porch in front of each unit, and a narrow entrance with passageway to discourage predators. Houses may be built of wood or metal. Purple Martins have been extensively studied due to their wide range, large population, and popularity with the public. Research shows that they are among the earliest returnees to North America in the spring, likely arriving in NE Ohio in April. These birds were photographed on May 17, 2022 at the Winous Point Shooting Club and the affiliated Marsh Conservancy.* These birds are likely choosing accommodations for the nesting season and more birds may still be arriving on site from the south. * Shooting clubs on the shores of Lake Erie over the past 100 years have been the main drivers of marshland conservation. No marshes mean no ducks, and therefore no fall hunting. In fact, throughout the U.S. hunters and conservationists/naturalists have worked closely together to preserve and regulate our natural world to maintain the proper balance of forces and conserve species. Canon ESO R6 with RF 100-500mm with RF 1.4 extender at 420mm, 1/4000 sec, f/10, ISO 1600 This series centers on apartment #7, and the unit above, which may be #14 (tough to see the number!). Above a female, or perhaps an immature male, arrives at #7 to join a presumed female. Below they seem to be canoodling a bit, this group of images culled from a large set. In the image above, our male/female looks up at the apartment upstairs (so to speak) at what is clearly a male and female pair perched on their porch. In the image below he/she takes off for the upper unit. While the sex is not entirely clear, this could be a female confronting another female over the male, who has presumably staked out this apartment, and may have staked out a larger set of apartments. Or then again, an immature male may be trying out his stuff against an older male. Below the male is clearly making noise at the intruder, who lands nonetheless. In the image above, the presumed female in #7 watches in interest. Below a confrontation, this time with the resident male, while the female checks out the accommodations. Image below, our visitor from #7 returns home to check out his/her accommodations! A careful observer will see that the male at the upper apartment and the male/female from #7 are both banded on the right leg. Although this often indicates a male of the species, especially in studies where the two sexes look alike (such as Cordilleran Flycatchers on Mt Lemmon), this is not always the case. For banding on Kelley's Island on Lake Erie banding is always done with a metal band on the right leg (ref: Andy Jones). So, the band leg does not really help us here, other than we know they are being tracked and studied. Older territorial male Purple Martins arrive early at nest sites, with females arriving later. This may be an instance of a single dominant male presiding over a number of units being visited by newly arriving females. Purple Martins eat flying insects at all times of year. Although birdhouse manufacturers advertise that martins can routinely eat greater than 2,000 mosquitoes a day, there is no credible evidence that martins eat mosquitoes at all (ref: Birds of the World). Martins fly high and during the day, mosquitoes fly low and mostly at night. My thanks to Andy Jones and Jeff Babson, who both reviewed this group of images as I was trying to figure out what this all meant. Juvenile males look like females, and banding in Ohio does not really help with sex identification. So, could be a young male, could be a female. Great Blue Heron RookeryCanon ESO R6 with RF 100-500mm with RF 1.4 extender at 700mm, 1/1000 sec, f/10, ISO 640 On May 15, 2022, we stopped by a Great Blue Heron rookery on West Bath Road, just north of the Akron Sewer Department just north of Akron, and south of Cleveland. See the map below. The rookery is at the yellow box, indicating where these pictures were shot. If you are taking a trip to Cuyahoga Valley National Park, this rookery is to the south of the park and worth a side trip. There were multiple nests high up in the trees adjacent to West Bath Road. In the images above the map and below we see an adult Great Blue Heron with three nestlings. Because of the high location, it was impossible to see into the nest. (For more rookery shots, see my post on the Smith Oaks Rookery, High Island, Texas in April 2019). Canon ESO R6 with RF 100-500mm with RF 1.4 extender at 700mm, 1/1000 sec, f/10, ISO 640 In the images above and below, an adult is flying back to the nest, likely with a crop full of fish. The adult regurgitates food onto the nest, where the nestlings gobble it up. Above, we see the characteristic S-shaped neck as the adult flys , with the short, wide tail, and long legs following behind. As the bird comes in for a landing, the legs droop like huge landing gear, and the wings flare out for a controlled stall. In the above photograph the alula, or "bastard thumb" is laid flat, and the associated feathers are lighter than the rest of the leading edge, right where the wing angles back. More on the alula below. Above and below, coming in for a landing. In the image above we again see the alula now extended or deployed to increase lift as the bird lands. About 40% of the bird's wing is distal to the wrist; all the "hand" bones are fused. The small feathers that jut up at the wrist on both sides are the alula, the heron equivalent of our thumb. The heron drops in for a landing on the nest, well camouflaged among the branches. Below an adult heron brings in a stick for ongoing nest maintenance. If you stop at this viewing point on W. Bath Road, park off of the pavement and watch for traffic in both directions. It is a busy road. DunlinCanon ESO R6 with RF 100-500mm with RF 1.4 extender at 700mm, 1/4000 sec, f/10, ISO 2000 Late in the afternoon of Monday May 16, 2022 we stopped in the Metzger Marsh area where migrating Dunlins were foraging for food in the mud. Dunlins are a North American shorebird that winter (non breeding) in coastal areas from Mexico up through the U.S. and Canada on both the east and west coasts. They are named after their color in the off season, a mousy gray-brown of "dun" color, seen below in a shot I captured last October in Cape May, New Jersey. However, in breeding season they develop a vivid rusty back and a black belly patch. This coloration at one time led to the name "Red-backed Sandpiper." However this bird drew the off-season card, and ended up "dun." In fact, the name comes from the word dunling, the earliest known English name of the species. "Dun" meaning gray brown, and "ling" the diminutive; it is literally a "little brown job." Dunlin in non-breeding plumage, Cape May, N.J., October 2021. In this series of photographs from the marsh in May, we see the bird foraging in the mud for invertebrates. Dunlins have very sensitive bill tips which enable them to detect prey by touch, allowing them to feed at night and take advantage of tidal cycles. References report they insert their bills only about a 1/4 inch or less to find prey, including earthworms, marine worms, midges, flies, craneflies, beetles, spiders, snails, mussels and small clams. I would say that this bird is defying the all my references and going more than a 1/4 inch deep! We can see the build-up of mud on his bill! Dunlins are quite beautiful in breeding plumage. They breed all the way north in the Arctic on the northern shores of Canada and Alaska. They nest in the subarctic or arctic tundra in wet areas, feeding close to where they nest. This bird is likely on his way north, stopping in Ohio for some rest and food. Below an image I captured at Cape May last October. In the winter Dunlins roost and forage in large flocks near saltwater, in this case, Cape May, N.J. All these birds are in winter plumage. Semipalmated PloverCanon ESO R6 with RF 100-500mm with RF 1.4 extender at 700mm, 1/2500 sec, f/10, ISO 2500 Not far from the Dunlin we spotted this Semipalmated Plover. This North American shorebird, similar to the Dunlin, winters along the the Pacific and Atlantic coasts, as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and portions of the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of South America. They breed in Northern Canada and Alaska, so presumably the winter residents of coastal Argentina are long range migrants, following the food along the shoreline to North America and then joining the rest of the population to migrate north across most of the lower 48 states and Canada to their nesting territory. This bird, like the Dunlin, is in migration, stopping in the marshes of Lake Erie to rest and feed. The name Semipalmated Plover comes from the partial webbing between their toes ("semipalmated"), not a very useful field mark! However, in the image below, captured on the Texas Coast in April of 2019, I think we can see a hint of the partial webbing on the right foot as this plover lifts his leg walking the beach. Semipalmated Plovers eat mostly small invertebrates, foraging in quick dashes followed by a pause to look and listen for prey. They like wetlands, beaches and agricultural fields, rarely wading into water over an inch deep. They were once on the decline because of hunting but have rebounded in recent years, in part because of their wide-ranging diet, flexible choices for foraging locations, and some special features such as large eyes which help them to forage at night, especially in moonlight. It is interesting that both Dunlins and Semipalmated Plovers have adaptions to forage at night, a real advantage nutritionally. Semi-palmated Plovers have been described as looking like small Killdeer (also plovers) with only one ring on the neck. So, to show these similarities and differences, here are some images of a Killdeer recently captured at Canoa Ranch in SE Arizona. And for contrast, a Killdeer from Canoa RanchCanon ESO R6 with RF 100-500mm with RF 1.4 extender at 700mm, 1/2000 sec, f/10, ISO 2000 The Killdeer is a plover. In fact, it is the only Plover without plover in its name. Its name comes from the bird's call, "kill deer!" Killdeer have two black neck bands, and a bright red/orange ring around the eye. Here we see one wading and feeding at the pond at Canoa Ranch on April 19, 2022. Whoa! That is it for NW Ohio in May 2022. We saw close to 200 species during the one week trip; I photographed about 80. The sampling of images in these 5 posts are the best of the lot with the best stories. To see more, plan a trip to Ohio next spring; you will not be disappointed.

More from SE Arizona soon! Happy Trails!

6 Comments

Linda Currin

8/3/2022 03:20:12 pm

Of course so fascinating, informational, and incredible photos! I probably won't be going to Ohio, so thanks for taking me along on your trip!!

Reply

Henry

8/3/2022 05:50:39 pm

Thanks!

Reply

cvr

8/3/2022 05:13:37 pm

Nice job Henry - I have never seen plastic purple martin houses - the shore bird with food is spectacular.

Reply

Henry

8/3/2022 05:49:38 pm

The plastic houses were really common in northern Ohio, almost every park had one or more clusters set up. The Dunlin's in breeding plumage were beautiful - really different from the nondescript "LBJ's" in the fall.

Reply

Janet L Davies

8/6/2022 06:57:35 am

Very beautiful birds and the stories that goes with them are precious.

Reply

Henry

8/6/2022 07:42:25 am

Jan, Thanks!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHenry Johnson, photographer and author of this site. For more detail, see About

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed